24-02-2017 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here

Adrift and directionless

Can MGNREGA move from being a ‘living monument of UPA’s failure’ to a development scheme?

The question, then, is what has changed for Modi and Jaitley? Have they realised the importance of the scheme as a safety net to fall back on during drought years, or are they going to turn it from essentially a dole into a development scheme?

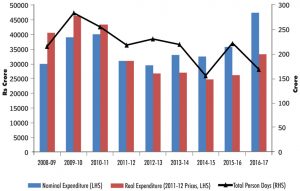

Since FY09, when the scheme had a pan India roll out, expenditure for MGNREGA has grown at an average of 7% per annum in nominal terms. But in real terms measured at 2011-12 prices (by using CPI-AL as deflator), it has actually been decreasing till FY15, and then improved marginally. Still, the budgeted expenditure in FY18 is roughly about 28% lower than the revised estimate of FY10 in real terms (see graph).

But how has the scheme performed in terms of creating employment opportunities in the last nine years? During periods of drought when marginal farmers and labourers alike are most vulnerable, MGNREGA is supposed to work as a social safety net by offering assurance of employment and income. In FY10, the number of households given employment and the total person days generated was the highest (see graph, RHS), owing to 2009 being a drought year. But this hasn’t been the case in recent years.

MGNREGA failed to serve as a fall back option for the poor during two consecutive droughts in 2014 and 2015. In fact the figure shows MGNREGA in FY15 generated the least number of person days and household employment since the start of the scheme. Although the following year saw an increase, it went down again in FY17.This happened despite the government’s January 2016 announcement that it would increase the number of days from 100 to 150. Thus, the scheme as a safety net did not come up to expectations in providing relief to poor workers and even marginal farmers during the drought of FY15.

However, it is interesting to observe that across states, the impact of MGNREGA has been ironically better in the relatively well-off states and worse in the poorer states. In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where poverty levels are about 30% of the state population and which also hold a third of India’s poor – the level of employment created by MGNREGA has been disappointing.Average number of days provided in both UP and Bihar were 34 and 45 days in FY16, the second year of back to back drought. These person days were much below the promised 100 days of employment. Contrast this with richer states like Tamil Nadu where average number of days of employment in FY16 was 61.

It is evident that lack of governance and high leakages in the poorer states is leaving the impoverished even more vulnerable. It is also interesting to note that the female participation in MGNREGA has gradually improved from 48% in FY09 to 57% in FY17 at all-India level. However, in Tamil Nadu and Kerala it is above 80%, but remains much lower in states like Assam, UP, Bihar and Odisha.MGNREGA also suffers from untimely delivery and poor quality of assets created. The FM’s announcement to construct another five lakh farm ponds under the scheme gives no assurance of quality and utility. The lack of a proper evaluation of asset quality by a third party leads us to the question whether MGNREGA has the potential for being an investment oriented model.

With so much spent on the scheme, the returns from it in areas like irrigation have not been satisfactory. Moreover, work completion rate is also a concern. Of the target 12.4 lakh farm ponds in FY17, so far only 4.5 lakh (or 37%) have been constructed. The promise to build more farm ponds in this budget is simply pushing ambition higher than is achievable.

Nevertheless, it isn’t as if the government is lacking the drive to improve the scheme. The June 2016 agreement between the ministry of rural development and Isro to geo-tag all assets constructed under MGNREGA is the right step ahead. Use of space technology to monitor and identify completed and under construction assets will not just improve outcome realisation but also transparency and accountability.

MGNREGA’s geo-tag platform ‘Bhuvan’ is a user interactive visual interface that provides information on the assets already constructed. However it is still at an infant stage and the FM’s claim that it has established transparency is a bit premature.Moreover it still remains unclear what direction MGNREGA is headed towards. Its near decade long experience does not bring much solace. Real expenditure has decreased; the scheme’s performance during droughts has been mixed; and assets constructed are mostly inferior. If the government is to avoid the embarrassment of MGNREGA becoming a living monument of NDA’s failure, it must do more than just hiking up allocations.

Ashok Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Sameedh Sharma is Research Assistant at ICRIER

आधार का दुरुपयोग

Date:24-02-17

बुनियादी क्षेत्र में निजी निवेश पर जरूरी है नीतिगत परिवेश

अब वक्त आ गया है कि बुनियादी ढांचा विकास में निजी क्षेत्र के निवेश को बढ़ावा देने के लिए नीतिगत माहौल तैयार किया जाए। कैसे किया जा सकता है यह काम, बता रहे हैं विनायक चटर्जी

निकायों का चुनावी मॉडल और सुशासन की चुनौती

Learn the lesson

HRD ministry’s return to PISA is welcome. Now, use the comparative data generated to reform school education.

Anyway, PISA is not a contest. It is a research exercise generating data which can be compared across borders. Finishing last should not be read as losing face, but rather as an opportunity to improve teaching methods and school systems by intelligent comparison. If Singapore’s systems work better, what prevents Indian school boards from emulating them? India lost out by boycotting PISA in 2012 and 2015, when Asian countries like China, South Korea and Singapore surged ahead. India need not have missed the bus, but the HRD ministry tried to change the benchmark to fit the country, rather than trying to change the country’s teaching system to fit the benchmark.While PISA is not a contest, it does have one competitive aspect: It is a reliable indicator of the future intellectual capital of participating countries. At one remove, it is a function of projected GDP, a reflection of the future wealth of nations. A country hoping to win the global GDP race should regard PISA as a target. And it should try to correct the structural imbalance that this test for schoolchildren draws attention to: India swears by universities and IITs, but it is happy to let primary and secondary schools, which form the bedrock of the education system, plod along with teaching methods that are decades old. The NDA government has done well to seek to return to PISA’s global testing system. But the crucial reform still lies ahead: PISA data must be used to improve the school system.

Date:23-02-17

Court self-corrects

SC decision on surveys critical of judiciary is a step towards bringing contempt provision in line with spirit of democracy.

In 2006, a report published by the Indian chapter of the international non-profit Transparency International and the Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies (CMS) drew the displeasure of a judicial magistrate in Jammu and Kashmir. The report, based on a survey of litigants across the state, was about the corruption in the J&K subordinate judiciary. The head of Transparency International and the CEO of CMS were issued notices under the provisions of the Contempt of Court Act, 1971. Eleven years later, the Supreme Court has quashed the notices on the ground that the subordinate courts do not have the power to issue warrants for contempt of court. But this technicality aside, the remarks of the three-judge bench led by Chief Justice J.S. Khehar, are significant. The court noted that a report based on public views regarding corruption may not invite contempt of court and such surveys, instead, give opportunities to address problems in the judicial system. For an agency that has often been accused of a thin skin in the face of criticism, the apex court’s verdict shows a welcome inclination to self-correct.

The contempt of court provision most often serves to keep the judiciary outside the ambit of public opinion. The judiciary’s view that such insularity is necessary to ensure its credibility as an impartial arbiter is understandable. But in times when the courts are playing an active role in shaping public policy — and also because the public has a general interest in the administration of justice — there are bound to be demands for making judges more accountable. These demands have acquired weight with charges of corruption against individual judges in the last five years or so. In 2013, in another poll by Transparency International, 45 per cent of those surveyed described the judiciary as corrupt. That year, Justice P. Sathasivam, before taking over as the Supreme Court Chief Justice, regretted that “the judiciary is not untouched by corruption”.On Tuesday, the three-judge bench remarked that surveys of the judiciary were also ways to “understand society”. “Instead of taking offence at such surveys, the judiciary should look at them closely and find ways to remedy the problems,” the bench noted. The Contempt of Court Act is a colonial relic that does the judiciary’s reputation more harm than good. Its arbitrary use has a chilling effect on free speech, especially at a time when the space for dissent is seen to be shrinking. Much more remains to be done to bring the contempt of court provision in line with the demands of a modern democracy. Tuesday’s verdict could be a beginning.

Ageing with dignity

While India’s celebrated demographic dividend has for decades underpinned its rapid economic progress, a countervailing force may offset some of the gains from having a relatively young population: rapid ageing at the top end of the scale. This is a cause of deep concern for policymakers as India already has the world’s second largest population of the elderly, defined as those above 60 years of age. As this 104-million-strong cohort continues to expand at an accelerating pace, it will generate enormous socio-economic pressures as the demand for healthcare services and tailored accommodation spikes to historically unprecedented levels. It is projected that approximately 20% of Indians will be elderly by 2050, marking a dramatic jump from the current 8%. However, thus far, efforts to develop a regime of health and social care that is attuned to the shifting needs of the population have been insufficient. While more mature economies have created multiple models for elder care, such as universal or widely accessible health insurance, networks of nursing homes, and palliative care specialisations, it is hard to find such systemic developments in India. Experts also caution that as the proportional size of the elderly population expands, there is likely to be a shift in the disease patterns from communicable to non-communicable, which itself calls for re-gearing the health-care system toward “preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative aspects of health”.

Advocacy and information campaigns may be necessary to redirect social attitudes toward ageing, which often do not help the elderly enjoy a life of stability and dignity. As highlighted in ‘Uncertain Twilight’, a four-part series in The Hindu on the welfare of senior citizens, the ground realities faced by the elderly include abandonment by their families, destitution and homelessness, inability to access quality health care, low levels of institutional support, and the loneliness and depression associated with separation from their families. On the one hand, the traditional arrangements for the elderly in an Indian family revolve around care provided by their children. According to the National Sample Survey Organisation’s 2004 survey, nearly 3% of persons aged above 60 lived alone. The number of elderly living with their spouses was only 9.3%, and those living with their children accounted for 35.6%. However, as many among the younger generation within the workforce are left with less time, energy and willingness to care for their parents, or simply emigrate abroad and are unable to do so, senior citizens are increasingly having to turn to other arrangements. In the private sector, an estimated demand for 300,000 senior housing units, valued at over $1 billion, has led to a variety of retirement communities emerging across the country, in addition to innovations in healthcare delivery for this group. Yet the poor among the elderly still very much depend on the government to think creatively and come up with the resources and institutions to support their needs.

Corrections & Clarifications: A sentence in the Editorial previously, read: “It is projected that approximately 20% of Indians will be elderly by 2050, marking a dramatic jump from the current 6%. The current percentage of elderly population is 8.