30-01-2018 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here.

Transition Pangs

Economic Survey says growth will improve, but education and agriculture need attention

TOI Editorials

The highlight of the Economic Survey unveiled yesterday is that economic growth is expected to gain momentum in 2018-19 after two years of deceleration. Prepared by the finance ministry, the Survey forecast that the economy will grow at a pace of 7-7.5% next year as against 6.75% in the current year. Over the last couple of months, high frequency indicators such as vehicle sales and industrial output suggested that the shock imparted on account of demonetisation and transition to Goods and Services Tax (GST) has worn off. That is a good sign for the economy.

But the most interesting aspect of the Survey is its analysis of India’s long-term challenges. Finding answers to them will determine how quickly prosperity percolates and growth becomes inclusive. Agriculture, which employs 49% of the workforce while making up just 16% of the economy, is in trouble. In addition to the age-old challenge of low productivity, it is being buffeted by a new one: climate change. The outcome will be a loss of income in agriculture, particularly for poorer farmers without the cushion of irrigation.

Linked to this problem is the sorry state of education in India. The growing influence of technology on economic activity and thereby employment is disruptive for an unskilled workforce. The best way to cope is quality education. Unfortunately, the Survey’s research shows that India’s learning poverty headcount, a measure of children who do not meet basic yardsticks, is roughly where overall poverty was 40 years ago. Even as India’s poverty reduced when measured in terms of consumption, it remains stuck in the 1970s when seen from the standpoint of learning. India’s future economic trajectory will depend on the success with which governments tackle these challenges.

Governments at all levels are aware of challenges ahead and there have been haphazard attempts to solve them. This now requires a more coherent approach which fits into the overall reform package that brings in more scientific methods into agriculture and simultaneously fixes the malfunctioning welfare system. To illustrate, instead of free electricity if farmers can get a cash transfer, irrational exploitation of depleting groundwater resources can be avoided. These reforms are the only way for India to get past its current transition phase that has been labelled by the Survey as “crony socialism to stigmatised capitalism”.

कम कीमत के जाल से कैसे बचें किसान

कृषि का वाणिज्यीकरण बढऩे और बाजार के समय के साथ नहीं बदल पाने के कारण किसानों की समस्याएं बढ़ती जा रही हैं।

रमेश चंद , (लेखक नीति आयोग और 15वें वित्त आयोग के सदस्य हैं।)

देश में कृषि क्षेत्र की वृद्घि दर पर इस क्षेत्र की कारोबारी स्थितियों का गहरा प्रभाव है। इस बात के प्रमाण हैं कि जब कृषि जिंसों की आरंभिक कीमतों में उतार-चढ़ाव रहा है, कृषि उत्पादन में खूब इजाफा हुआ है। देश में कृषि वृद्घि की मूल्य पर निर्भरता इसलिए है क्योंकि गैर मूल्य कारक और प्रौद्योगिकी प्रभाव नहीं डाल पा रहे। जब तक ये कारक वृद्घि के वाहक नहीं बनते, तब तक हमें उत्पादन और कृषि आय में वृद्घि के लिए मूल्य को ही कारक बनाए रखना होगा। ऐसे में अगर बाजार प्रतिस्पर्धी नहीं हैं और साल दर साल उत्पादन बढ़ता है तो सरकार की मदद आवश्यक है। न्यूनतम समर्थन मूल्य (एमएसपी) एक अहम सरकारी हस्तक्षेप है। जिसकी मदद से कृषि उपज का मूल्य बेहतर किया जाता है। यह व्यवस्था सन 1965 में विकसित की गई थी ताकि देश में खाद्यान्न की कमी दूर की जा सके। शुरुआत में केवल धान और गेहूं के लिए एमएसपी घोषित किया गया ताकि उत्पादकों को उत्पादन बढ़ाने के लिए प्रेरित किया जा सके। हरित क्रांति के तहत यह अन्न उत्पादन सरकारी खरीद की उपलब्धता सुनिश्चित करने के क्रम में किया जा रहा था। बाद में अन्य फसलों को भी इसमें शामिल किया गया और फिलहाल 23 फसलों पर एमएसपी दिया जाता है। इसमें कपास, जूट, तिलहन, दालें और प्रमुख खाद्यान्न शामिल हैं। बहरहाल, अन्य फसलों के लिए कोई प्रभावी तंत्र नहीं बन सका और एमएसपी का प्रभाव गेहूं, चावल और कपास तक सीमित रहा। वह भी उन राज्यों में जहां सरकारी एजेंसियां इन्हें खरीदती हैं।

आंकड़ों से पता चलता है कि देश के विभिन्न इलाकों में कई कृषि जिंसों की किसान को मिलने वाली कीमत अक्सर एमएसपी से कम रहती है। एमएसपी को लेकर जागरूकता बढऩे के साथ कई किसानों ने इसकी मांग शुरू कर दी। खेती के बढ़ते वाणिज्यीकरण और बाजार में बदलाव की कमी ने किसानों को कम कीमत से बचाव की मांग पर मजबूर किया। वर्ष 2016-17 के बंपर उत्पादन के बाद फसल कीमतों में एक बार फिर गिरावट आई और इस साल भी ऐसा ही होने की उम्मीद है। यही वजह है कि अब हर फसल के लिए एमएसपी की मांग उठ रही है। यह मांग दो वजहों से उचित है। पहली, एमएसपी की अधिसूचना सरकार जारी करती है इसलिए उसे उसका मान रखना होता है और दूसरा कृषि मूल्य एवं लागत आयोग एमएसपी की घोषणा करते वक्त जिन संदर्भों का ध्यान रखता है वे आर्थिक और तकनीकी रूप से तार्किक होते हैं। एमएसपी को लेकर कोई भ्रम नहीं है लेकिन यह तय होना चाहिए कि एमएसपी का सम्मान हो, केंद्र और राज्य मूल्य गारंटी तय करने की दिशा में काम करें और राजकोषीय तथा बाजार प्रभावों का ध्यान रखा जाए।

सरकार द्वारा एमएसपी पर की जाने वाली खरीद के अलावा कृषि एवं किसान कल्याण मंत्रालय भी दो अन्य योजनाएं चलाता हैं। इसमें चावल, गेहूं और कपास के अलावा अन्य एमएसपी फसलों के लिए मूल्य समर्थन योजना तथा गैर एमएसपी फसलों के लिए बाजार हस्तक्षेप की नीति। ये योजनाएं राज्यों द्वारा केंद्र के साथ लागत साझेदारी के आधार पर चलनी होती हैं। इसी तरह कई तरह की खरीद मूल्य स्थिरीकरण फंड और उपभोक्ता मामलों के विभाग के बफर स्टॉक योजना के तहत की जाती है। इन योजनाओं का दायरा सीमित है। किसानों को मिलने वाली कम कीमत की समस्या को दूर करने के लिए कृषि एवं किसान विकास मंत्रालय ने मार्केट एश्योरेंस स्कीम नामक योजना तैयार की। इसमें सुझाव दिया गया कि गेहूं और चावल के अलावा एमएसपी में अधिसूचित अन्य फसलों की विकेंद्रीकृत खरीद की जाए। यह काम राज्यों के जिम्मे छोड़ दिया जाए। केंद्र सरकार उन्हें होने वाले किसी भी नुकसान की भरपाई करे। यह खरीदी गई जिंस के एमएसपी के 40 फीसदी तक होगा। इसमें हर तरह का व्यय, भंडारण व्यय तथा होने वाला कोई भी नुकसान शामिल है।

सरकारी खरीद को एमएसपी लागू करने के तरीके के रूप में प्रयोग में लाना महंगा है। इसका एक अहम विकल्प यह है कि मूल्य में नुकसान की भरपाई कर दी जाए। इस व्यवस्था में जब भी तयशुदा मंडी में किसान को मिलने वाली वास्तविक कीमत तय एमएसपी से कम हो तो सरकार उन्हें इस अंतर की भरपाई कर सकती है। मध्य प्रदेश सरकार ने भावांतर भुगतान योजना नाम से इसकी शुरुआत की है। किसानों को एमएसपी और औसत आदर्श मूल्य के बीच का अंतर भुगतान किया जा रहा है। यह औसत बाजार मूल्य मध्य प्रदेश तथा दो पड़ोसी राज्यों में उपज की औसत कीमत के आधार पर निकाला जा रहा है। यह योजना आकर्षक प्रतीत होती है और इसमें आगे और सुधार करके इसे विभिन्न राज्यों और विशिष्टï फसलों के अनुरूप बनाया जा सकता है। हरियाणा सरकार ने पहले ही एमएसपी से आगे चार सब्जियों आलू, प्याज, टमाटर और गोभी के लिए इस वर्ष मूल्य में कमी के भुगतान की योजना प्रस्तुत कर दी है। देश के कृषि क्षेत्र की व्यापकता और फसलों की विविधता को देखते हुए केंद्र अकेले सभी प्रमुख फसलों के लिए मूल्य गारंटी सुनिश्चित नहीं कर सकता। ऐसे में केंद्र और राज्य दोनों की ओर से सक्रिय हस्तक्षेप की आवश्यकता है ताकि किसानों को कम कीमत और उसकी वजह से उपजी निराशा से उबारा जा सके। केंद्र को यह सुनिश्चित करना चाहिए कि वह गेहूं और धान की एमएसपी पूरे देश में तय करे। ऐसा इसलिए क्योंकि ये फसलें खाद्य सुरक्षा की दृष्टिï से बहुत महत्त्वपूर्ण हैं। देश की कुल फसलों के रकबे में 37 फीसदी के साथ ये फसले शीर्ष पर हैं। राज्यों को चाहिए कि वे शेष फसलों के लिए मूल्य गारंटी योजना को लागू करने की दिशा में कदम बढ़ाएं। वे इसकी लागत को केंद्र के साथ साझा कर सकते हैं।

राज्य सरकारों को या तो केंद्र की मार्केट एश्योरेंस योजना अपनानी चाहिए या फिर मध्य प्रदेश और हरियाणा की मूल्य अंतर भुगतान योजना को अपनाना चाहिए ताकि किसानों को अपनी फसल की वाजिब कीमत तो मिल सके। जिन फसलों को अहम माना जाता है उनके लिए यह योजना लाई जानी चाहिए। ऐसा करने से किसानों को अपनी उपज की कम कीमत मिलने से जो निराशा हो रही है वे उससे निजात पा जाएंगे। इसका उत्पादन वृद्घि पर भी सकारात्मक असर होगा। किसानों को उनकी उपज का बेहतर मूल्य दिलाने में सबसे अहम भूमिका प्रतिस्पर्धी बाजार की है। इसके लिए सभी राज्यों को बाजार सुधारों को अपनाना चाहिए। इस संबंध में राज्य केंद्र शासित प्रदेश कृषि उपज और पशुधन विपणन (संवद्र्घन एवं सुविधा) अधिनियम 2017 में सुझाया भी जा चुका है।

अधिक जरूरी है आर्थिक और राजनीतिक सशक्तीकरण

संपादकीय

राष्ट्रपति रामनाथ कोविंद ने बजट सत्र के अभिभाषण में सड़क निर्माण, किसानों की आय दोगुनी करने और रोजगार उत्पादन करने संबंधी सरकार की उपलब्धियों और योजनाओं का वर्णन करने के साथ जिन दो प्रमुख बातों पर ध्यान दिया है उनमें संसद और विधानसभाओं के चुनाव एक साथ कराने की मंशा और अल्पसंख्यकों का तुष्टीकरण करने की बजाय उनका सशक्तीकरण करना है। निश्चित तौर पर ये दोनों मुद्दे सत्तारूढ़ भाजपा और विशेष तौर पर प्रधानमंत्री नरेंद्र मोदी के अपने मुद्दे हैं और इन पर सहमति बनाना आसान नहीं है। प्रधानमंत्री ने पिछले दिनों चैनलों को दिए अपने संपादकीय में कहा था कि एक साथ चुनाव कराने की वजह सिर्फ चुनाव खर्च ज्यादा होना ही नहीं है बल्कि चुनाव के दौरान बढ़ने वाली कटुता भी है। चुनाव के दौरान पक्ष और विपक्ष में बहस के दौरान तल्खी पैदा होती है। यह तब और बढ़ जाती है जब हर साल दो-चार राज्यों में चुनाव होते हैं, जिससे देश का संघीय ढांचा बहुत प्रभावित होता है। संसद-विधानसभा के चुनाव का सुर-ताल 1967 के बाद बिगड़ा और तब से ठीक ही नहीं हो पा रहा है। शायद भाजपा को यह भी लग रहा है कि अगर देशभर के चुनाव एक साथ हुए तो नरेंद्र मोदी जैसे ओजस्वी वक्ता और पार्टी की विशाल चुनाव मशीनरी के माध्यम से वे देश की केंद्रीय सत्ता और सभी राज्यों पर कब्जा कर लेंगे। लेकिन सांस्कृतिक और सामाजिक विविधता के कारण इस देश के राजनीतिक ढांचे में एक प्रकार की बहुलता रहेगी। वह दूसरे आम चुनाव से झलकने लगी थी और तीसरे तक स्पष्ट हो गई थी। इसलिए इस मामले पर सभी दलों को कुछ न कुछ कीमत चुकानी होगी। दूसरा अहम मसला अल्पसंख्यकों का है और सरकार ने संकल्प जताया है कि वह तीन तलाक विधेयक हर कीमत पर इस सत्र में पारित करके रहेगी। सरकार को यह सोचना होगा कि वह अल्पसंख्यकों के तुष्टीकरण से परहेज करके तो धर्मनिरपेक्षता का भला कर रही है लेकिन, बहुसंख्यकों का तुष्टीकरण करके संविधान और देश दोनों का भला नहीं कर रही है। जहां तक अल्पसंख्यकों के सशक्तीकरण की बात है तो वह सांस्कृतिक और सामाजिक से ज्यादा राजनीतिक और आर्थिक क्षेत्र में किए जाने की आवश्यकता है। वैसे यह बात सभी वर्गों पर भी लागू होती है, जिसकी ओर एनडीए सरकार का ध्यान कम है।

कृषि बाजार में नई संभावनाएं तलाशने की जरूरत

राणा प्रताप सिंह, प्रोफेसर, एन्वायरन्मेंटल साइंस

ताजा अंतरराष्ट्रीय सर्वेक्षणों के अनुसार देश के जिन लोगों की आय एक प्रतिशत या कम बढ़ी है, उनमें अधिकांश किसान और मजदूर हैं, जो अनेक नई-पुरानी शासकीय योजनाओं के बावजूद लगभग उतने ही अभावग्रस्त हैं, जैसा पहले थे। उनकी आमदनी बढ़ाने का कोई स्पष्ट, पारदर्शी और प्रामाणिक तरीका सफल नहीं हो पाया है।

खेती, खाद्यान्न, किसान एवं कृषि मजदूरों की समस्या आज स्वतंत्रता प्राप्ति के शुरुआती दशकों से अलग है। हरित क्रांति के हाइब्रिड बीजों, सिंचाई साधनों के विस्तार और रासायनिक खादों व कीटनाशकों के प्रयोग ने कृषि उपज इतनी बढ़ा दी कि खाद्यान्न सुरक्षा बड़ी चुनौती नहीं रह गई। आज कृषि क्षेत्र की असली चुनौती कृषि पैदावार और बाजार भाव में अनिश्चय की स्थिति और उत्पादों का सही भंडारण व कृषि उत्पादों की बिक्री के लिए स्थानीय विपणन नेटवर्क का उपलब्ध न होना है। जलवायु परिवर्तन व बढ़ती महंगाई के दौर में किसानों को खेती से पर्याप्त आय न मिल पाने से लोग खेती-बारी से दूर होते जा रहे हैं। जहरीले रसायन रहित खाद्य पदार्थों व आवश्यक पोषण वाले कृषि उत्पादों का प्रतिशत बढ़ाकर कृषि और खाद्य-जन्य घातक बीमारियां नियंत्रित करना बड़ी चुनौती है। कृषि जनित चुनौतियों पर नीतिगत विवेचना और कार्य योजनाएं तो कम हैं ही, इन पर चर्चा भी कम ही होती है।कृषि में उन्नत तकनीक के प्रयोग मात्र से किसानों की आय दोगुनी करना संभव नहीं है। हालांकि ग्रीन हाउस, पाली हाउस व नेट हाउसों वाली संरक्षित कृषि, बहुमंजिली खेती, ड्रिप इरिगेशन वाली खेती तथा अलग-अलग मौसम वाले बीजों की आवश्यकता तथा सौर ऊर्जा से संचालित उपकरण कृषि लागत घटा सकते हैं। ये उपाय कृषि उत्पादन की अनिश्चितता कम कर, प्राकृतिक संसाधनों के संरक्षण में मददगार बन सकते हैं, लेकिन तब, जब उत्पादक से उपभोक्ता तक विपणन का सही नेटवर्क बन पाए।

आवश्यक है कि उन भौगोलिक क्षेत्रों में, जिनमें प्रति एकड़ अधिक उत्पादन का लक्ष्य कृषि रसायनों के अधिकाधिक प्रयोग के बावजूद नहीं मिल पाया है, जैविक या कम रसायनों वाली जैविक व रसायन मिश्रित खेती, नई कृषि तकनीक व एक नया विपणन तंत्र विकसित किया जाए। जैविक खेती पद्धति को बढ़ावा देने से हमें न सिर्फ अविषाक्त खाद्य पदार्थ प्राप्त होंगे, बल्कि इसमें डाले जाने वाले खाद व कीट प्रबंधन के उपायों के लिए स्थानीय स्तर पर बड़ी संख्या में रोजगार भी उत्पन्न होंगे, जो स्थानीय ग्रामीण युवकों को शहर जाने से रोक सकेंगे। इन लघु उद्योगों में न सिर्फ ग्रामीण, बल्कि छोटे कस्बों के युवक भी सम्मिलित होकर अपने रोजगार के साधन बढ़ा सकेंगे।

प्रबंधन तंत्र के विकास का लाभ कृषि क्षेत्र को सबसे कम मिला है। न कृषि में लगने वाली उन्नत तकनीक और मशीनों की मार्केटिंग का उचित ढांचा व माहौल बना, न कृषि उत्पादों की व्यापक मार्केटिंग के लिए मार्केटिंग प्रबंध के नए ज्ञान का पर्याप्त रूप से इस्तेमाल किया जा सका है। किसानों की आय बढ़ाने, कृषि उपज को बाजार की जरूरतों के अनुसार नियंत्रित करने के लिए नई तकनीक से भी ज्यादा जरूरी स्थानीय विपणन नेटवर्क, मुख्य बाजार व बड़े शहरों से कृषि उत्पादों को जोड़ना है। कृषि उत्पादों की छंटाई, पैकिंग, सप्लाई चेन व अल्पकालीन भंडारण को लेकर गांवों-कस्बों के युवा नए स्टार्टअप बना सकते हैं। उन्हें उचित ज्ञान, प्रोत्साहन व संरक्षण की जरूरत है। हालांकि बहुराष्ट्रीय और विदेशी कंपनियां ऐसे नए बाजारों की पहचान कर रही हैं, पर वे इसमें हाथ तभी डालेंगी, जब ग्रामीण और शहरी मध्य व निम्न मध्यवर्ग के हाथ में गुणवत्तापूर्ण खाद्य पदार्थ चुनने की प्रवृत्ति जगेगी और इनके पास पैसा आएगा। अभी तो सामाजिक और सरकारी प्रयासों को ही इस दिशा में गति देनी होगी।

हरित क्रांति के दौर से ही हमारे देश में नीतिगत और कार्यकारी तौर पर सारा जोर फसलों की उत्पादकता बढ़ाने पर रहा। स्वतंत्रता प्राप्ति के बाद के दो-तीन दशकों में इसकी आवश्यकता भी थी। हरित क्रांति की कृषि नीतियों से धान व गेहूं की पैदावार तो बढ़ी, परंतु भंडारण, खरीद, संग्रह और विपणन के प्रभावी ढांचे नहीं बन पाए। किसानों की लागत बढ़ी, उपज भी, पर उनका शुद्ध लाभ अनाजों के उत्पादन बढ़ने से नहीं बढ़ा, किसानों की आय तो गन्ना, केला, सेब जैसी व्यावसायिक फसलों से बढ़ी है।

Wealth and Hindutva

For the BJP, one is for rich and the other is for poor

Udayan Mukherjee, [ The writer is consulting editor with CNBC-TV18 ]

It is Budget season and there is the usual chatter in the well-heeled circles of Mumbai and Delhi about the possibility of “draconian” measures such as a long-term capital gains tax on shares, an inheritance tax or a wealth tax. Ironic, as this comes at a time when an Oxfam report has just told us that the richest 1 per cent of Indians accounted for 73 per cent of the total gain in national wealth last year. Yet, the rich want more. And they cannot bear the thought of the government claiming an extra portion of their fortunes, however tiny.

Ordinary hard-working, salaried folk part with over a third of their annual income, in the highest tax bracket. Income from bank fixed deposits, where most of Indian savings lie, is taxed at the same rate. But when you make a killing in the stock market, as most investors have over the last few years, you pay nothing, long-term capital gains tax being zero. Apparently, this is to encourage financialisation of savings. In a country where the poor go hungry, is this conscionable? Yet, the government cannot bring itself to take this step as it may break the breathtaking flight of the Sensex, which conveys to the world India’s great economic success. Inequality is just a leftist lament, the things which matter are GDP growth and the Sensex, correct?

The Oxfam report says we now have 101 billionaires. We should be proud of them. Thirty-seven per cent of these billionaires are inheritors of family wealth. For years, there has been background noise on an inheritance tax but the government has not had the guts to implement it. Meanwhile, most inheritors have protected their acquired wealth through the creation of trusts in a way that even an inheritance tax may not be able to reach. The Maharajas may have disappeared from the scene but economic feudalism lives on, and thrives.Oxfam says that the wealth of the richest 1 per cent of Indians grew by Rs 21 lakh crore last year, roughly the size of India’s annual budget. Would it not be fair to tap a very small portion of this obscene number, as wealth tax? Just a drop of this enormous bounty for Indians who are less fortunate? Unimaginable. The finance minister has already soothed the anxieties of billionaires by promising that there won’t be any such tax.

Not just individuals, corporate India wants its share too. Lobbyists of CII and FICCI are working overtime to ensure that the rate of corporate tax is slashed in the budget, in line with an earlier commitment. Apparently, this is necessary to unleash “animal spirits” in our best companies, and of course to further fuel the Sensex. All lofty objectives. In essence, the portion of our country which has the most — wealthy citizens and profitable corporations — should get the biggest benefits from economic policy, that is the pitch.It is logical to be baffled. At a time when economic growth has slowed, unemployment and inequality have jumped and the government is struggling to find budgetary resources, surely the onus must fall on the haves to help out the have nots? Equally, for a government preparing for a national election, one would have thought its priorities would be directed at the larger population — the ones who did not see their wealth balloon last year. Yes, but there is a flaw in that line of reasoning. The premise that economics is the key determinant for a voting choice across all sections of society is seen as a bogus one by the government.

Economics matters, for urban India. The BJP understands the economic pulse of the urban Indian voter better than any other party. A sharp fall in the Sensex can spoil the mood. Any claim on the growing wealth of the rich can affect the feel good factor. This cannot be disturbed. Modi hails from Gujarat, he understands it.But what about rural India? Our farmers, small businessmen, wage labourers, the jobless? For them, there is the opium of the masses — religion. After four years of falling short, the BJP knows that it cannot go back to the larger, non-urban electorate with economic delivery as its election plank. For this section, achhe din still remains a mirage and any mention of it may actually rile sentiments. We saw glimpses of it during the recent Gujarat elections. Much more prudent, then, to fall back on good old Hindutva to win votes in the crucial Hindi heartland. The choice of Yogi Adityanath as the chief of India’s most populous state is the biggest proof of Modi’s conviction that Hindutva trumps economics any day, in the villages of north India.

This is why, while there may be some overtures to farmers and the rural population, analysts should not fear a hugely populist budget from Arun Jaitley. Some additional outlays here and there but nothing game-changing. And stock investors should breathe easy, nothing will be done to rock their boat. Villagers and farmers, on the other hand, should not expect any great turnaround in their fortunes. Rather, they should expect more instigation to emerge more patriotic and more Hindu, and cement their “rightful” domination of this great nation. What is money, after all, compared to these far loftier ideals?Next year there will be another survey to show how the gap between the rich and poor has grown even wider. Yet, nothing will be done about it. Because our prime minister has cracked the winning formula. Horses for courses: More wealth for the rich, Hindutva for the poor.

Date:29-01-18

How to help the farmer

Price deficiency payment schemes in Madhya Pradesh and Haryana do not cover farmers’ losses. Telangana’s input support scheme deserves nation-wide emulation.

Ashok Gulati & Siraj Hussain, [Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Hussain is former secretary, agriculture, GoI, and currently visiting senior fellow at ICRIER.]

Farm distress is likely to be one of the major focal points of the upcoming Union Budget. Agri-GDP growth has fallen to around 2 per cent per annum in the first four years of the Modi government; the real incomes of farmers have fallen as well. The growth in the agriculture sector is much below the Centre’s target and the government does not seem to be on course to double farmers’ incomes by 2022. With assembly elections in 10 states due later this year, the states going to the polls are making attempts to woo farmers. While some have announced loan waivers, others are trying to fix farmers’ woes emanating from tumbling farm prices. Here, we focus on two pilot projects to see if they can be scaled-up at the all India level.

The first is the Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana (BBY), essentially a price deficiency payment (PDP) scheme, being undertaken by the government of Madhya Pradesh. BBY applies to eight kharif crops — soybean, maize, urad, tur, moong, groundnut, til, ramtil. The Haryana government has announced a somewhat similar scheme for four vegetables — potatoes, onions, tomatoes and cauliflower. The second pilot scheme we talk about is underway in Telangana, where the government gives all farmers an investment support for their working capital needs.

Under the BBY, farmers have to first register on a portal. Their sown area is verified by government officials. They are then asked to bring their produce to mandis at a time fixed by the state government. Based on average productivity of a crop in the district and area cultivated by the farmer, the quantity of each produce that is eligible for deficiency payment is also determined by the government. Farmers receive the difference between average sale price (ASP) and MSP directly into their bank accounts. The scheme seems interesting as it provides an alternative to physical procurement of commodities at minimum support prices (MSPs). The ASP is calculated as the simple average of the weighted modal prices of the relevant crops in the regulated mandis of Madhya Pradesh and two adjoining states. The price information is drawn from the Centre’s agmarknet.gov.in portal.

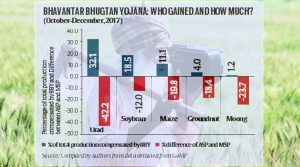

For kharif 2017-18, so far, data related to five crops (soybean, maize, groundnut, urad and moong) has been finalised for price deficiency payment. The market prices of til and ramtil are higher than the MSP and therefore they do not qualify for price deficiency payment. The tur season will start from February.The graph shows the key results of BBY for October-December, 2017. It is interesting to note that only 32 per cent of urad production in Madhya Pradesh got the yojana’s benefit despite the fact that ASP of urad was 42 per cent below its MSP. In other words, 68 per cent of urad production was sold at prices below MSP, without any compensation under BBY. In the case of soybean, the state’s prime kharif crop, the percentage of production benefiting from this scheme is even lower — only 18.5 per cent, despite its ASP being 12 per cent below the MSP. And for maize, groundnut and moong, the coverage is even poorer (see graph).

The Madhya Pradesh government claims to have paid about Rs 1,900 crore as compensation to farmers for these five crops. But that pertains to only those farmers registered on its portal. A larger proportion of farmers are not registered on the portal and they have been selling their produce at huge losses. These farmers have not received any compensation. In fact, those not registered under BBY have to suffer bigger losses because traders are suppressing the market. We have calculated their loss by multiplying the production not covered under BBY with the price difference between MSP and ASP. The actual prices in Madhya Pradesh are even lower than the ASP, which is the average of modal prices of three states. The total loss for these five crops comes to Rs 6,534 crore. So, if the scheme was fully successful and covered entire production, the Madhya Pradesh government’s revenue outgo would be Rs 8,434 crore, and not Rs 1,900 crore. This would be more than 90 per cent of the state’s total budget for agriculture. In sum, BBY is not inclusive, covers less than 25 per cent of the farmers’ loss, involves too much micro-management by government officials and is prone to market manipulation.

Haryana’s scheme for four vegetables is even worse as the presumed MSP (Rs 400 per quintal for potatoes and tomatoes and Rs 500 per quintal for onions and cauliflower) does not even cover the full cost of production as estimated by the Union Ministry of Agriculture and the National Horticulture Board for these crops.In contrast to these programmes is the government of Telangana’s input support scheme. Announced in the second week of January, the scheme’s objective is to relieve farmers from taking loans from moneylenders by giving them Rs 4,000 per acre for the kharif and rabi seasons. It is envisaged that the farmer will use this money for purchase of inputs ranging from seeds to fertilisers to machinery and hired labour. The area eligible for investment support is 14.21 million acre — the government’s annual bill for the project, thus, comes to around Rs 5,685 crore.

The Telangana model does not require the farmer to register his cultivated area and crops. The farmer is free to grow a crop of his choice and sell it anytime in a mandi of his choice. This model is crop-neutral, more equitable, more transparent, and gives farmers the freedom to choose. Incidentally, China has a similar scheme: It gives aggregate input subsidy support on a per acre basis. The scheme does not distort markets and is worth following. Will the Union Budget make such a bold move to redress farmers’ woes?