28-12-2016 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here

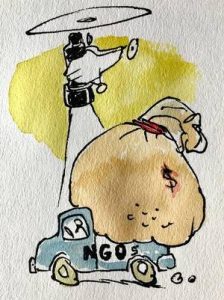

Time to repeal the FCRA

The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, is nothing more than a tool to keep ‘errant’ civil society organisations on a tight leash. An autonomous, self-regulatory agency for NGOs is the need of the hour

The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government has defended its action by claiming that these organisations had violated FCRA norms by engaging in activities detrimental to public interest. But its decision has drawn criticism from different quarters.

Civil society members have issued statements condemning the move, charging the government with “abuse of legal procedures”. Opposition MPs from six political parties have written to the Prime Minister questioning the government’s motives, and termed it “a decision motivated by the politics of vendetta, victimisation and an effort to bully them into silence”. The National Human Rights Commission has issued a notice to the Home Ministry, observing, “Prima facie it appears FCRA licence non-renewal is neither legal nor objective and thereby impinging on the rights of the human rights defenders in access to funding, including foreign funding.”

Despite the censure, the NDA regime has shown no signs of relenting. This mass cancellation of FCRA licences is not the first time that the legislation has been used thus. In 2015, the Home Ministry had cancelled the FCRA licences of 10,000 organisations. Prominent international funding agency Ford Foundation, the environmentalist group Greenpeace, and human rights advocacy group Lawyers Collective have all been targets of FCRA-linked curbs on their activity, suggesting a larger pattern in the way the state has used this law.

The origins of the FCRA

The original Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act was enacted in 1976 by the Indira Gandhi-led government during the Emergency. It prohibits electoral candidates, political parties, judges, MPs and even cartoonists from accepting foreign contributions. As the inclusion of ‘cartoonists’ under its ambit suggests, the intent was to clamp down on political dissent.

The ostensible justification given for the law was to curb foreign interference in domestic politics. This was the Cold War era, when both the Soviets and the Americans meddled in the internal affairs of post-colonial nations to secure their strategic interests. Amid suspicions of the ubiquitous ‘foreign hand’ stoking domestic turbulence, the FCRA was aimed at preventing political parties from accepting contributions from foreign sources.

As the years passed, India seemed to overcome its suspicion of the ‘foreign hand’. It embraced foreign funding by opening up the economy in 1991. The Indian state had no problem accepting contributions from foreign donors such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. With the state wooing foreign investment, Indian businesses, too, helped themselves to foreign funds. And so did our political parties, despite the FCRA, 1976, expressly prohibiting them from accepting money from ‘foreign sources’.

Both the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress were pulled up by the Delhi High Court in 2014 for violating the FCRA by accepting contributions from the Indian subsidiaries of the London-based multinational, Vedanta. It ordered the government and the Election Commission to take action against both the parties. To no one’s surprise, the BJP-led NDA government did not take action against the BJP. Nor did it do so against the Congress, which, as the leading Opposition party, did not think it appropriate to protest this flagrant flouting of a judicial directive.

Instead, earlier this year, the government quietly introduced a clause in the Finance Bill that amended the relevant section of the FCRA, 2010, so that what was hitherto a “foreign company” now became an Indian company. This amendment was introduced with retrospective effect — a brazen attempt to legitimise the FCRA violations of the two parties. This amendment has also opened the doors for all political parties to accept funding from foreign companies, so long as it is channelled through an Indian subsidiary.

It may be pertinent to point out here that it was the Congress, under the stewardship of Manmohan Singh, that replaced the original FCRA, 1976, with a more draconian version in 2010. But why the new law? To answer that question, we need to consider the differences between the two legislations.

The new FCRA

Human rights activist Venkatesh Nayak draws attention to three changes that render the new Act more stringent than the old one. Firstly, FCRA registration under the earlier law was permanent, but under the new one, it expired after five years, and had to be renewed afresh. This instantly hands the state a whip with which to bring errant organisations to heel.One may recall that earlier this year, 11,319 NGOs lost their FCRA licences without the government having to either examine their records or suspend their registrations individually — their licences simply expired as the deadline for renewal passed.

Second, the new law put a restriction (50 per cent) on the proportion of foreign funds that could be used for administrative expenses, thereby allowing the government to control how a civil society organisation (CSO) spends its money.The third and most important distinction is that while the 1976 law was primarily aimed at political parties, the new law set the stage for shifting the focus to “organisations of a political nature”. The FCRA Rules, 2011, framed by the United Progressive Alliance government, has served the NDA well as a manual on how to target inconvenient NGOs, especially those working on governance accountability. It helpfully enumerates the kind of organisation that could be targeted under the FCRA as “an organisation of a political nature”.

The list is revealing: trade unions, students’ unions, workers’ unions, youth forums, women’s wing of a political party, farmers’ organisations, youth organisations based on caste, community, religion, language and “any organisation… which habitually engages itself in or employs common methods of political action like ‘bandh’ or ‘hartal’, ‘rasta roko’, ‘rail roko’ or ‘jail bharo’ in support of public causes”.

Institutionalising double standards

Put simply, a political class that has no qualms taking money from foreign sources, that amended the FCRA to let itself off the hook for past violations, that opened the doors for all political parties to accept foreign funding, that paved the way for Indian businesses to access foreign capital, is now anxious to prevent CSOs from accessing foreign funds because some of them question its policies in a democratic battle to protect constitutional rights and entitlements.

Last April, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association undertook a legal analysis of the FCRA, 2010. He submitted a note to the Indian government which stated unambiguously that the FCRA provisions and rules “are not in conformity with international law, principles and standards”.

The UN Special Rapporteur’s argument was fairly straightforward. The right to freedom of association is incorporated under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a party. Access to resources, particularly foreign funding, is part of the right to freedom of association. While this is not an absolute right and is subject to restrictions, those have to be precise, and defined in a way that “would enable a CSO to know in advance whether its activities could reasonably be construed to be in violation of the Act”.

The report says that restrictions in the name of “public interest” and “economic interest” as invoked under the FCRA rules fail the test of “legitimate restrictions”. The terms are too vague and give the state excessive discretionary powers to apply the provision in an arbitrary manner. Besides, given that the right to freedom of association is part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 20), a violation of this right also constitutes a human rights violation.

Does all this mean that the FCRA should be repealed? If yes, how then do we monitor the foreign funding of NGOs?Of course, NGO funding needs to be regulated. One cannot deny that corrupt NGOs exist, or that unscrupulous NGOs that receive foreign funds may serve as conduits for money laundering. But there are better ways to address these concerns than an FCRA that institutes an ‘Inspector Raj’ for the NGO sector.

In fact, a seven-member task force was set up way back in 2009 to create a national-level self-regulatory agency, the National Accreditation Council of India (NACI), that would monitor and accredit CSOs. It was to be an independent, statutory body along the lines of the Bar Council. The task force submitted its report to the Planning Commission in September 2010. It was never heard of again. Instead, what we got in September 2010 was a more aggressive FCRA. Perhaps it is time to repeal the FCRA and revive the idea of an autonomous, self-regulatory agency for CSOs.

sampath.g@thehindu.co.in

अग्नि परीक्षण

अग्नि-5 के इस परीक्षण को मिसाइल तकनीक व नियंत्रण संधि से भी जोड़कर देखा जाएगा। इस साल अक्तूबर में ही भारत इस संधि में शामिल हुआ था। इसके पहले तक जब भारत कोई मिसाइल परीक्षण करता था, तो पश्चिमी देश उसका विरोध इस बिना पर करते थे कि वह बिना मिसाइल संधि पर दस्तखत किए परीक्षण कर रहा है। हालांकि इस संधि में शामिल होना न्यूक्लियर सप्लायर्स ग्रुप में शामिल होने जितना कठिन भी नहीं था, जहां चीन उसका रास्ता रोककर खड़ा है। कुछ अन्य कारणों से इटली ने जरूर एक बार भारत को इसमें शामिल होने से रोका, अन्यथा भारत के लिए कोई बाधा थी ही नहीं, क्योंकि चीन अभी तक इस संधि में शामिल हुआ ही नहीं है। भारत अब बिना रोक-टोक इस तरह की मिसाइल तकनीक विकसित कर सकता है, बल्कि संधि के सदस्य देशों से उनकी तकनीक ले भी सकता है या उन्हें तकनीक दे भी सकता है। एक समय था, जब इस संधि पर दस्तखत न करने के कारण भारत को रूस से मिसाइल तकनीक हासिल करने से रोक दिया गया था। भारत ने खुद इसकी तकनीक विकसित की, इसमें बहुत कुछ हाथ उस रोक का भी था।

मिसाइल तकनीक के मामले में भारत की कामयाबी हमें हैरत में भी डालती है और गौरव बोध भी देती है, लेकिन कुछ सवाल भी खड़े करती है। इतनी उन्नत तकनीक विकसित करने वाला हमारा देश छोटी-छोटी रक्षा तकनीक के मामले में क्यों दूसरे देशों का मुंह देखता है? क्यों हम आज भी दुनिया के सबसे बडे़ हथियार आयातक बने हुए हैं? हम आकाश से मार करने वाले एक से एक मिसाइल बना रहे हैं, लेकिन छोटी तोप और मशीनगन तक के मामले में हमें दूसरे देशों पर निर्भर रहना पड़ता है। यहां तक कि हमें इजरायल जैसे छोटे देशों तक से हथियार खरीदने पड़ रहे हैं। मिसाइल और रॉकेट तकनीक के क्षेत्र में हमने जो सफलता हासिल की है, उसे रक्षा के दूसरे क्षेत्रों तक कैसे ले जाया जाए, यह हमारी सबसे बड़ी चुनौती है। रक्षा सामग्री के मामले में आत्मनिर्भर न होना एक ऐसी बाधा है, जो विश्व शक्ति बनने के हमारे संकल्प का रास्ता रोक सकती है।