21-11-2017 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here.

Date:21-11-17

Date:21-11-17

Parliament first

State elections aren’t a persuasive reason for central ministers to skip Parliament

TOI Editorials

The delay in announcing dates for Parliament’s winter session, held during the third week of November by tradition, smacks of disdain for a positive legacy. The notification summoning the two Houses is issued around 2-3 weeks in advance so that MPs have adequate time to provide notice for questions and reach Delhi. So by November 2 the President should have summoned Parliament. The delay has raised questions about the government’s conduct. With no official explanation forthcoming, a plausible reason is the Gujarat assembly election campaign in which Prime Minister Narendra Modi is heavily invested.

The Constitution mandates that gap between two sessions cannot exceed six months. Since monsoon session ended on August 11, the government can proceed to the budget session without violating constitutional strictures. But the convention of starting tri-annual sessions – budget, monsoon and winter – around loosely fixed dates harks back to 1955. Allowing such vital norms of parliamentary functioning to lapse because of contingencies like assembly polls sets a bad precedent. Congress has termed it an “assault on parliamentary democracy” and accused the government of ducking tough questions on GST and economy. But it was Congress that thwarted established convention in 2008 by deferring the monsoon session to October-November leaving no room for a winter session after scraping through a controversial trust vote that witnessed the cash-for-votes scandal.

In 2016, Parliament had 70 sittings against just 48 this year. Contrast this to the first Lok Sabha which averaged 135 sittings a year. Parliament is as much about legislating as debating and asking questions that hold governments to account. The lack of enthusiasm also implicitly reveals that government has no pressing legislative agenda either. There is merit in Trinamool Congress leader Derek O’Brien’s suggestion to fix parliamentary calendar at the year’s start so that politicking doesn’t interfere with lawmaking.

![]() Date:21-11-17

Date:21-11-17

Make philanthropy serious business

ET Editorials

Infosys non-executive chairman Nandan Nilekani and his wife Rohini have joined the growing list of billionaires who have committed to give away at least half of their wealth to philanthropic causes through The Giving Pledge campaign, founded by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. They join Wipro’s Azim Premji, Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw and P N C Menon of the Sobha Group in this list. This is good news and will encourage others to donate generously to help rid the world of its many ills. In an interview to this newspaper, Nilekani said that he sees philanthropy as an extreme risk capital. And that unlike government or market money, an individual’s charity can be written off if something does not work. Individual goodwill is laudable. But why, pray, should that kind of moolah, which can do serious good, be written-off?

Billionaires should use skills that helped them make their fortune to organise spending the money to generate an optimal impact. Nilekani, who helped Infosys grow into a multibillion-dollar revenue giant, knows this best. The Nilekanis hope to direct much of their giving to societal platforms or tech-enabled collaborative initiatives involving government and other stakeholders. New strategies in giving, and alliances are welcome.There are niggling worries, too. Will charity help address some of the flaws of the voluntary sector, given that many have been ensnared in controversies? Will it bring in more transparency in their operations? Also, will charities be interested in resolving country-specific problems? In India, for example, fighting diseases calls for safe drinking water, improved personal hygiene, maternal and children’s health and proper nutrition that don’t entail billion-dollar fixes. Givers must ensure that the focus is on what requires to be done in each country.

Date:21-11-17

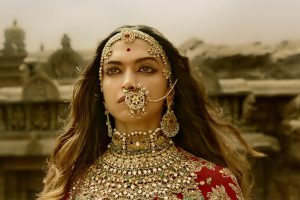

Film critics can’t break the law

ET Editorials

One conspicuous absence in the ongoing episode involving the demand of a ban on/deletion of ‘offending’ scenes of/bounty on the head of an actor in — choose your pick —Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmavati is any guarantee from many of those entrusted with upholding the law of this country that those threatening to break the law will be thwarted. As the law of the land stands, there is nothing unlawful about protesting against a film, or even demanding that it be consigned to the ash heap of cinematic history. Neither is there anything unlawful about making a movie — unless, according to the statutory body assigned for exactly that job, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), deems it, or parts of it, ‘unfit’ to be screened.

What is unlawful, illegal and downright criminal are the threats of violence being made, and condoned, all in the name of ‘popular will’. The Bamiyan Buddhas, it may be recalled, were blown up by a different bunch in Afghanistan also in the name of ‘being offended’. It is remarkable how much those baying for ban and blood for apparently ‘insulting’ a legendary Rajput queen resemble the demonically prosaic Taliban.

Political stalwarts, from Madhya Pradesh’s BJP chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, who encouraged protesters by ‘banning’ the film in his state even before the CBFC’s verdict, to his Punjab counterpart Amarinder Singh, who supported those protesting the feature film’s ‘distortion of history’, have been fanning a dangerous flame. Quite unlike their Maharashtra and Karnataka counterparts, who have already deployed security to those involved in the production of Padmavati as well as against those threatening violence.Bhansali and his colleagues have not aired any intent to insult. Many of his voluble critics, however, have aired their intent to cause violence — to property, body and life. Once again, for whatever reason, people have the right to protest, even against perceived slights. But if they threaten to break the law, law keepers would be deluded to think that by cow-towing to ‘the people’s will’ alone will keep them popular and safe beyond tomorrow.

एनजीटी के निष्प्रभावी तौर-तरीके

डॉ. भरत झुनझुनवाला [लेखक वरिष्ठ अर्थशास्त्री एवं आइआइएम बेंगलुरु के पूर्व प्रोफेसर हैं ]

नेशनल ग्रीन ट्रिब्यूनल यानी एनजीटी ने पंजाब, हरियाणा और पश्चिमी उत्तर प्रदेश के खेतों में पराली जलाने पर प्रतिबंध लगाया, लेकिन वह निरर्थक साबित हुआ, क्योंकि एनजीटी ने किसानों की मूल समस्या को नजरअंदाज किया। पराली जलाने की समस्या इन राज्यों की विशेष परिस्थितियों के कारण उत्पन्न होती है। पश्चिम बंगाल से तुलना करने पर यह बात स्पष्ट हो जाती है। बंगाल में हर वर्ष 3.6 करोड़ टन पराली होती है। इसकी तुलना में पंजाब में यह दो करोड़ टन ही होती है, लेकिन बंगाल में पराली नही जलाई जाती है जबकि पंजाब में जलाई जाती है। इसी प्रकार लगभग पूरे देश में धान का उत्पादन होता है, परंतु पंजाब, हरियाणा और पश्चिमी उत्तर प्रदेश को छोड़कर अन्य कहीं बड़ी मात्रा मे पराली नही जलाई जाती है। पंजाब में पराली जलाने का मूल कारण श्रमिक की दिहाड़ी का ऊंचा होना है। पंजाब में सरकार द्वारा घोषित खेत मजदूरी की न्यूनतम दिहाड़ी 293 रुपये है जबकि बंगाल मे 213 रुपये। मेरा अनुमान है कि पंजाब मे धान की कटाई के समय वास्तविक दिहाड़ी 400 रुपये होगी जबकि बंगाल मे 200 रुपये। पराली को इकट्ठा करने में श्रम ज्यादा लगता है। गेहूं का भूसा थ्रेशर से छोटे टुकड़ों मे निकलता है जिन्हें ट्राली में भरकर किसान आसानी से घर ले आता है। इसके उलट पराली लंबे टुकड़ों मे निकलती है। मेरा अनुमान है कि यदि किसी ट्राली में दो टन भूसा लोड किया जा सकता है तो पराली मात्र आधा टन। उतनी ही पराली को घर लाने में ट्राली को चार चक्कर लगाने पड़ते हैं। भंडारण के लिए जगह भी बड़ी चाहिए। यही समस्या पराली से कागज बनाने में खड़ी हो जाती है। खेत से फैक्ट्री तक पहुंचाने के लिए पराली को मशीन से गांठ में बांधना पड़ता है। तब ही ट्रक में पर्याप्त मात्रा में पराली को लोड किया जा सकता है। बंगाल में श्रम का मूल्य कम होने से पराली को घर लाकर पशुओं को खिलाना अथवा फैक्ट्री तक पहुंचाना आसान है। इसकी तुलना में पंजाब में खर्च ज्यादा आता है, क्योंकि वहां श्रमिक की दिहाड़ी ऊंची है। इसलिए पंजाब में पराली को जलाया जाता है।

पंजाब में समस्या और ज्यादा विकराल हो जाती है, क्योंकि धान की कटाई और गेहूं की बुआई के बीच मात्र 15 दिन का समय मिलता है। इस समय श्रमिकों का उपलब्ध होना ज्यादा कठिन होता है। किसान को खेत से पराली हटाकर गेहूं की बुआई के लिए जुताई जल्दी करनी होती है। इसलिए वह पराली को जला देता है। दूसरी ओर बंगाल में धान की एक फसल के बाद धान की ही दूसरी फसल लगाई जाती है जो कि हर समय चलती रहती है। इसलिए किसी विशेष समय बंगाल में पराली का अत्याधिक उत्पादन नही होता है। पराली के उत्पादन एवं श्रम की उपलब्धता में भी संतुलन बना रहता है। पंजाब की समस्या का हल यह है कि भारतीय खाद्य निगम यानी एफसीआइ पराली का उपयुक्त दाम निर्धारित करे जिससे ठेकेदारों के लिए पराली को किसान के खेत से उठाकर गांठ बनाकर निगम के गोदाम तक पहुंचाना लाभप्रद हो जाए। जिस प्रकार ईंट बनाने के लिए ठेकेदार झारखंड से मजदूर को केरल ले जाते हैं उसी प्रकार पराली की गांठ बनाने के लिए वे बिहार-झारखंड के मजदूरों को पंजाब ले आएंगे। निगम को पराली की गांठों को देश के दूसरे क्षेत्रों में गौपालकों अथवा कागज फैक्ट्रियों को बेच देना चाहिए। इस व्यापार में निगम को घाटा लगेगा। यदि यह व्यापार लाभप्रद होता तो व्यापारी इसे स्वयं कर लेते। यह घाटा सरकार को वहन करना होगा। समय के साथ ही पराली की गांठों का राष्ट्रीय बाजार बन जाएगा। तब निगम का घाटा कम हो सकता है।

पराली की समस्या का दूसरा हल यह है कि धान की कटाई को विशेष प्रकार के हार्वेस्टर से करने को लाभप्रद बनाया जाए। वर्तमान हार्वेस्टर में पराली के लंबे टुकड़े निकलते हैं जो खेत में ही फैले रहते हैं। इनके स्थान पर ‘सुपर स्ट्रा मैनेजमेंट सिस्टम’ वाले हार्वेस्टर का उपयोग करना चाहिए। इन उन्नत हार्वेस्टर से पराली के छोटे टुकड़े निकलते हैं जो खेत में फैले रहते हैं और जुताई के समय दब जाते है। समय के साथ ही ये खाद बन जाते हैं। तब किसान को खाद मुफ्त में मिल जाएगी और पराली को जलाने की जरूरत भी नहीं रह जाएगी, परंतु उन्नत किस्म के हार्वेस्टर की लागत ज्यादा आती है इसलिए किसान उसका उपयोग नहीं करना चाहते। इनके उपयोग पर सरकार को सब्सिडी देनी चाहिए।पराली की गांठों को खरीदने अथवा उन्नत हार्वेस्टर का उपयोग करने के लिए सब्सिडी केंद्र सरकार को देनी चाहिए, क्योंकि इन कदमों का लाभ दिल्ली समेत पूरे देश को होगा। पंजाब से यह अपेक्षा नहीं की जा सकती है कि वह दिल्ली को धुएं से मुक्त करने के लिए अपने राजस्व का उपयोग करे। इस दृष्टि से पंजाब के मुख्यमंत्री अमरिंदर सिंह की सब्सिडी की मांग जायज है, परंतु उनकी यह मांग कि सब्सिडी धान के एमएसपी में 100 रुपये प्रति क्विंटल की वृद्धि के रूप में दी जाए तो यह उचित नहीं है। किसान इस बढ़े हुए दाम को ले लेंगे, परंतु पराली जलाते रहेंगे, क्योंकि पराली के दोबारा उपयोग की मूल समस्या ज्यों की त्यों बनी रहती है। समस्या का समाधान केंद्र सरकार द्वारा एफसीआइ तथा उन्नत हार्वेस्टरों पर सब्सिडी देकर ही निकल सकता है। दुर्भाग्य से ऐसा लगता है कि एनजीटी की पराली की समस्या को समझने एवं हल निकालने मे रुचि नहीं है। केवल हवाई आदेश पारित किए जा रहे हैं कि पराली जलाने पर प्रतिबंध है। ये आदेश वैसे ही हैैं जैसे बच्चों के चॉकलेट अथवा आइसक्रीम खाने पर प्रतिबंध लगा दिया जाए। एनजीटी का प्रयास रहता है कि दिल्ली की मध्यमवर्गीय जनता को प्रसन्न करे, किसान कष्ट सहे तो सहे।

अन्य मामलों में भी एनजीटी का यही हाल है। जैसे उत्तर प्रदेश का रेनूकूट-सिंगरौली क्षेत्र और महाराष्ट्र का चंद्रपुर तापीय बिजली संयंत्रों के कारण भट्ठी बन गया है। लोग रोगों से ग्रसित हो रहे हे, परंतु एनजीटी को उनकी सुध नहीं है। एनजीटी केवल उनके द्वारा छोड़े जाने वाले धुएं पर विचार कर रहा है। मूल विषय है कि देश के आर्थिक विकास के लिए कितनी बिजली की जरूरत है और इस जरूरत को पर्यावरण के न्यूनतम नुकसान से कैसे पूरा किया जाए। इन प्रश्नों पर एनजीटी मौन है। अतीत में एनजीटी ने पर्यावरण मंत्रालय को निर्देश दिया था कि विकास की सभी परियोजनाओं के लाभ हानि का समग्र मूल्यांकन करने के नियमों को बनाने के लिए कमेटी बनाई जाए। पर्यावरण मंत्रालय, भारतीय वन प्रबंधन संस्थान के अंतर्गत ऐसी कमेटी बनाई भी गई। कमेटी ने कहा कि थर्मल बिजली परियोजना का मूल्यांकन करने को बिजली से होने वाले लाभ एवं धुएं से होने वाली हानि का भी मूल्यांकन करना चाहिए। मंत्रालय को यह पसंद नही आया। मंत्रालय ने विज्ञप्ति जारी की कि केवल जंगल की हानि का मूल्यांकन जरूरी होगा। मंत्रालय के इस दुराग्रह पर एनजीटी मौन रहा और तमाम नुकसानदेह परियोजनाओं को दी गई स्वीकृति पर मुहर लगा दी। एनजीटी को चाहिए कि केवल दिल्ली की मध्यमवर्गीय जनता को प्रसन्न करने के स्थान पर पर्यावरण की मूल समस्याओं पर ध्यान दे।

Date:20-11-17

Date:20-11-17

Before 2020

Editorials

The 23rd Conference of Parties (CoP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was expected to be a low-key affair. The meeting, that began on December 6, in the German city, Bonn, was slated as a pit stop for next year’s CoP when the rule-book for the Paris Climate Change Treaty will be finalised. But like CoPs in the past eight years, the Bonn conference stretched into extra time because the participating nations were divided over the agenda of a pre-CoP meeting next year.This meet will assess whether the actions promised by the signatories to the Paris Agreement are adequate to meet the pact’s objectives. Throughout the 12-day long CoP 23, developed and developing countries squabbled on whether next year’s preparatory meet should also include an assessment of the progress made on climate change mitigation commitments before 2020, when the Paris pact will come into force.

The pre-2020 commitments are significant for emerging economies like India, China and Brazil. Unlike the Paris pact, the onus of fulfilling the pre-2020 obligations — reducing emission and providing finance and technology to the developing countries — lies on the developed countries. If these countries do not fulfil their obligations in the next three years, the emerging economies will have to take a greater share of the climate change mitigation burden after the Paris pact comes into force.But the developed countries have always been tardy about their pre-2020 commitments. A paper of the Climate Change Finance Unit of India’s Ministry of Finance, for instance, shows that the OECD countries have used creative accounting methods to exaggerate their annual climate mitigation aid to developing countries by more than 50 billion dollars.

At the CoP 23, the developed and developing countries could only reach a partial agreement. The developed countries will submit a report by May next year stating the progress on their pre-2020 commitments. As if on cue, 15 countries led by Canada and the UK formed a loose alliance to cut down their use of coal by 2030. For it to be effective, however, the alliance’s developed country members (the alliance does not include India and China) should be forthcoming with money and technology transfers in order to help reduce the dependence of developing countries on coal.iction over finances forced the Bonn conference to stretch more than half-a-day beyond its scheduled closing date. The CoP 23 declaration did finally mention financial and technology transfers. But that is, at best, a procedural victory for the developing countries. It will be at least six months before we know whether the developed countries have put their money where their mouth is.

Pacific Ocean’s 11

The revival of the Trans-Pacific Partnership minus the U.S. opens opportunities for India

EDITORIAL

When Donald Trump abandoned the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in his very first week after being sworn in as U.S. President, there were doubts whether the trade agreement, painstakingly negotiated over more than a decade, would survive. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had termed the TPP without the United States — which contributed 60% of the combined Gross Domestic Product of the 12 members — as “meaningless”. Ten months on, exactly at a time when Mr. Trump was visiting Vietnam, trade ministers from the remaining 11 nations agreed in Danang in principle to a new pact, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), revising some of the features of the TPP. For the agreement to take effect, the pact requires domestic ratification, which is expected to be complete by 2019. This major step taken by the 11 countries of the Pacific Rim excluding the U.S. is a reflection of two things. First, these countries recognise that multilateral free trade, contrary to any misgivings, is beneficial in the long run. The TPP in its current form has significant protections for labour and environment and is in this regard an advance over other free trade agreements. Second, the U.S.’s self-exclusion reflects a failure on the part of the Trump administration; studies have shown significant benefits in comparison to minor costs — in terms of jobs — to the U.S. on account of the pact.

As things stand, the pact without the U.S. can only be interpreted as yet another step that diminishes American power and the international order that it has so far led. Already, Mr. Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris climate accord and his repudiation of the Iran nuclear deal have raised suspicions about American commitment to well-negotiated treaties that seek to solve or have solved long-standing issues. Mr. Trump couches his regime’s policies as populist nationalism — ‘protecting labour’ in the case of the abandonment of the TPP, promoting jobs in fossil fuel-intensive sectors to justify the repudiation of the Paris Accord, and retaining American exceptionalism in West Asian policy in scrapping the Iran nuclear deal. While rhetoric to this effect had fuelled his presidential campaign with a heavy dose of populism, the actual effect of going through with these actions has been to create a suspicion among America’s allies about his reliability when it comes to standing by old commitments. Mr. Trump’s agenda to pull his country out of multilateral agreements has coincided, ironically, with the rise of China as the leading world power promoting globalisation. Now the ASEAN-plus-six Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), on which China is pushing for an agreement, could benefit from complementarities with the CPTPP. India, which is also negotiating the RCEP, must utilise this opportunity to win concessions on services trade liberalisation as part of the plan.

Date:20-11-17

More than just a counting game

Urban India must focus on more than toilets to address sanitation woes

Kavita Wankhade , works at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bangalore, and is part of the Tamil Nadu Urban Sanitation Support Programme (TNUSSP) in Chennai.

Yesterday, November 19, 2017, was World Toilet Day, with the theme ‘Wastewater and Faecal Sludge Management’. In India, there is greater awareness about the importance of using toilets, largely due to the high profile, flagship programme Swachh Bharat Mission launched in 2014, so much so that even Bollywood capitalised on this topic in the recent film Akshay Kumar starrer, Toilet — Ek Prem Katha, where a marriage is saved thanks to toilets. However, in real life, the sanitation story only begins with toilets, something clearly stated by the targets under the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals. These targets are not just about ‘toilets’ but also suggest improvements to the entire cycle of sanitation, which certainly begins with toilets but has to end with safe waste disposal.

Four stage cycle

Sanitation is intrinsically linked to health, and unless faecal waste is treated properly and disposed of safely, it will find its way back into our bodies and make us sick either by contaminating our sources of drinking water or getting into the food chain. The full cycle of sanitation has four stages: access to toilets; safe containment; conveyance either through the sewerage network or de-sludging trucks, and treatment and disposal. The faecal waste needs to be handled safely at each of these stages in order to gain public health benefits.

As recognised in the last decade, urban India faces considerable gaps along the full cycle of sanitation. One probable reason for these deficits was the belief that sewerage and sewage treatment systems could be built in all cities. Sewerage refers to fully sealed pipes, that are underground, and must not be confused with open storm water drains that are supposed to carry only rainwater. After decades of investment, India has managed to connect only a little more than a third of its urban households, most of which are located in metropolitan cities, to sewerage systems. This is because sewerage systems and sewage treatment plants (STPs) — a preferred system in most western countries — are not only expensive but are also complicated to maintain.

An alternative to sewerage systems is something known as on-site systems. Septic tanks and pit latrines, which are prevalent in many Indian households, fall into this category. If these systems are designed, constructed and managed properly, they can be perfectly safe options. Safe containment, collection and treatment is known as septage management or faecal sludge management (FSM), and is being increasingly recognised by the Government of India as a viable option.

Multi-stage challenges

Though viable, there are several challenges for FSM across all stages.

Emerging evidence from across the country indicates that on-site systems are not constructed properly. While the designs of ‘septic’ tanks and leach pits have been set out in standards issued in government documents, houseowners and masons are often not aware of these. The most severe consequence of these poorly designed pits is the potential contamination of groundwater. In addition, they are not de-sludged at regular intervals. Faecal waste needs to be transported using de-sludging vehicles (and not manually) but only some States, Tamil Nadu for example, have these vehicles. Once collected, the waste needs to treated properly to ensure that it does not land up in our lakes and rivers. There aren’t enough treatment facilities to guarantee proper treatment of the sludge.

A way forward

After the National Urban Sanitation Policy (NUSP) in 2008, a national policy on Faecal Sludge and Septage Management (FSSM) was released earlier this year. Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Odisha have released State-wide septage management guidelines and taken concrete steps to execute these policies. While de-sludging vehicles and robust informal markets exist for de-sludging services in some States, others are either procuring vehicles for their urban local bodies or encouraging private players to get into this.

Tamil Nadu has decided to utilise existing infrastructure, namely STPs, and allowed the co-treatment of faecal sludge in these facilities. It has also put in additional infrastructure called decanting stations at some pumping stations to make it easier for de-sludging vehicles to deposit their waste. Devanahalli in Bengaluru has a dedicated Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant (FSTP) operational since 2015. Others of varying sizes are either under construction or already running in Kochi (Kerala), Tiruchi (Tamil Nadu) and as far as Leh. Thus, there are many promising steps being taken, but much more needs to be done if we are to truly become an open-defecation free nation.Here are some suggestions that both the government and us, citizens, can work towards.

Raising awareness about correct design and construction practices of on-site systems (new and legacy) will perhaps remain the biggest hurdle in the years to come. But, urban local bodies and State governments could start by ensuring that the larger containment systems such as community toilets and public toilets are properly constructed and managed. In addition, permission could be granted to new buildings, especially large apartment complexes only when the applicants show proper septage construction designs. The safety of sanitary workers who clean tanks and pits must be ensured by enforcing occupational safety precautions and the use of personal protective equipment as set out in the law. The last two suggestions are actions for us as citizens. As home-owners and residents, our tanks and pits must be emptied regularly, thereby preventing leaks and overflow. We must ask our governments to invest in creating treatment facilities that our cities can afford.Let us move beyond the cute poop emojis on our smartphones and make this an acceptable discussion topic in the drawing room. Maybe the biggest victory will come when citizens realise that the focus needs to be on more than just toilets.