15-10-2019 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here.

Date:15-10-19

Date:15-10-19

Details Matter

Economics Nobel for Abhijit Banerjee and others as they developed a tool for impactful policy

TOI Editorials

Abhijit Banerjee yesterday became the second Indian origin economist to win a Nobel prize, 21 years after Amartya Sen was awarded one. Banerjee will share the prize with Esther Duflo, his partner in both professional and personal spheres, and Michael Kremer. They have been awarded the prize for their work on developing and refining an experimental approach to design programmes of poverty alleviation. One way of looking at it is that their contribution has been pragmatic. The tool they have evolved, randomised control trials (RCT), is widely used by researchers in development economics.

Banerjee and Duflo, 47, only the second woman and the youngest ever to be awarded the prize, have carried out extensive field trials in India. Their work has been used to design policy. The Delhi government’s education reforms are based on suggestions made by Banerjee. For policy makers RCT can be a useful tool to separate the signal from the noise and increase a policy’s efficacy. RCT has been adapted from medicine to gain an understanding of how people make decisions. Once policy makers understand the motivating forces underlying people’s choices, it becomes possible to improve policy designs. It is the bedrock of evidence based policymaking.

As a tool which improves policy design, RCT is based on theoretical foundations from multiple strands of economics, including behavioural economics. However, it is rare for work which fetches an economics Nobel to be free of criticism. RCT has its share of critics. It can be drilled down to the complaint that its efficacy is overstated and it is faddish. In contrast, significant amounts of economic theory seeks to answer big questions and work out general theories. The debate is between efficacy of micro level policy interventions and macro institutions.

From an Indian standpoint, this debate is misplaced. Big ideas do matter. They produce a coherent economic vision which can guide us. But India’s complex development experience shows much is lost between an idea and its implementation. It’s in this context that the work of Banerjee, Duflo, Kremer is important. Details matter. Policy design can make all the difference between success and failure. RCT is not a panacea for poverty alleviation. It is, however, an essential tool in getting things right. Therein lies the real contribution of Banerjee, a product primarily of the Indian education system.

Date:15-10-19

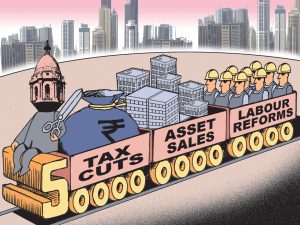

How To Do $5 Trillion By 2024

Next steps after corporate tax rejig: Cut personal taxes, reform labour laws, sell assets

Arvind Panagariya , [ The writer is Professor of Economics at Columbia University.]

In what is arguably one of the boldest reforms in the last 20 years, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has cut the effective tax rate on corporate profits from approximately 35% to 25.2% for existing domestic companies and 17% for new manufacturing companies established before October 31, 2023, provided the companies take no exemptions. For existing companies, the tax rate is now below or equal to those in Japan, South Korea, China, Indonesia and Bangladesh though higher than those in Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam and Singapore. For new manufacturing companies, the tax rate equals that in Singapore but is below those in all other countries just named.

By putting an end to exemptions, the government has greatly simplified the corporate profit tax system and thus eliminated numerous sources of bribes, harassment and tax disputes. Provided the government does not let exemptions slip back into the system, it would have limited future tax disputes to reporting of revenues and costs. Tax inspectors will no longer be able to harass enterprises and extract bribes from them by questioning the exemptions sought by them.

There is a strong case for a similar reform of personal income tax. Far too many exemptions, which erode the tax base, have led the government to increase the top effective marginal tax rate to 43%. High rates with loopholes embedded in exemptions invite corruption and harassment. Aligning the top personal income tax rate to the corporate profit tax rate at 25%, with all exemptions eliminated, would curb corruption and minimise tax disputes.

If the government credibly assures taxpayers that higher declared incomes on future tax returns will not form the basis of investigation of past reported incomes, reductions in tax rates will also yield higher, not lower, revenues. The expansion of tax base will offset the effect of the reduction in the tax rate.

The lower corporate profit tax means higher return on investment and hence greater incentive to invest. The demand for investment by corporations will rise. The lower tax rate would also translate in higher profits and hence higher corporate savings. Additionally, attracted by higher returns on corporate investment, households may channel more of their savings into financial markets.

Therefore, the tax cut promises to raise investment, especially in the formal sector. The only qualification is that the government must refrain from borrowing the additional financial savings and converting them into current expenditures.

In India, capital is a far scarcer factor of production than labour. Corporations can commonly be heard complaining about the high interest rates, but not high wages. Therefore, one would expect them to spread scarce capital over a large workforce. But one of India’s most enduring paradoxes is that its corporations do exactly the opposite, investing in the most capital intensive industries and technologies. For instance, in the auto sector, the largest single sector in manufacturing, the wage bill for all workers from the managing director down to the watchman accounts for less than 5% of the total cost.

India can ill-afford to squander its scarce capital in this manner. If creating good jobs is a priority for the nation, we need additional reforms that would nudge our corporations to spreading the nation’s scarce capital over many more workers. This points in the direction of labour law reforms. It is time that the government finally took this bull by the horns.

Minimally, the Prime Minister must personally see to it that the code on industrial relations, currently under preparation, ends the effective ban on the termination of workers by manufacturing enterprises employing 100 or more workers. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi introduced this archaic regulation four decades ago and it is time we bid goodbye to it.

Modi could follow the model he himself pioneered in the Special Economic Zones in Gujarat back in 2004. Under his leadership, the state returned to enterprises the right to terminate workers in its SEZs on the condition that they paid terminated workers 45 days worth of wages for each year worked.

From a short-run perspective, the large cut in corporate profit tax, which is predicted to result in revenue loss of up to 0.7% of the GDP, poses a dilemma for the government. If it leaves expenditure where it is, its fiscal consolidation will take a beating. If it cuts expenditure, the measure will be contractionary at a time when aggregate demand is already weak.

The way out of this dilemma is another set of important pro-growth reforms: strategic sales of public sector enterprises (PSEs); monetisation of infrastructure assets such as highways, airports, ports, railway stations and power transmission lines; and sale of unused government-owned urban land. PSE sales and asset monetisation have already been on the government’s policy agenda. It must now pursue this agenda vigorously, adding the sale of urban land to it.

By moving forward aggressively on these fronts, the government has the unusual opportunity to kill four birds with one stone: it will avoid slipping on fiscal consolidation; it will maintain the aggregate demand; it will greatly enhance efficiency of PSEs, infrastructure assets and urban land; and it will signal its resolve to move ahead towards a $5 trillion economy.

Missionaries of Clarity

The 2019 Economics Nobel laureates on free trade and growth from their forthcoming book

Abhijit V Banerjee & Esther Duflo , [ Banerjee is Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics, at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US, and Duflo is Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics, MIT. Both are founders of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) with Duflo as its director. Along with Michael Kremer, Gates Professor of Developing Societies, Harvard University, they are recipients of the 2019 Nobel Prize for Economics.]

Many of the issues plaguing the world right now are particularly salient in the rich North, whereas we have spent our life studying poor people in poor countries. It was obvious that we would have to immerse ourselves in many new literatures, and there was always a chance that we will miss something. It took us a while to convince ourselves that it was even worth trying.

We eventually decided to take the plunge, partly because we got tired of watching at a distance while the public conversation about core economic issues — immigration, trade, growth, inequality or the environment — goes more and more off-kilter. But also because, as we thought about it, we realised that the problems facing the rich countries in the world were actually often eerily familiar to those used to studying the developing world — people left behind by development, ballooning inequality, lack of faith in government, fractured societies and polity, and so on.

We learnt a lot in the process and it did give us faith in what we, as economists, have learnt best to do, which is to be hard headed about the facts, sceptical of slick answers and magic bullets, modest and honest about what we know and understand, and perhaps most importantly, willing to try ideas and solutions and be wrong, as long as it takes us towards the ultimate goal of building a more humane world.

A woman hears from her doctor that she has only half a year to live. The doctor advises her to marry an economist and move to South Dakota. Woman: ‘Will this cure my illness?’

Doctor: ‘No, but the half year will seem pretty long.’

Why Whisky and Rum Don’t Mix

The idea that free trade is beneficial is one of the oldest propositions in modern economics. As the English stockbroker and MP David Ricardo, explained two centuries ago, since trade allows each country to specialise in what it does best, total income ought to go up everywhere when there is trade, and as a result, the gains to winners from trade must exceed the losses to losers. The last 200 years have given us a chance to refine this theory, but it is a rare economist who fails to be compelled by its essential logic. Indeed, it is so rooted in our culture that we sometimes forget that the case for free trade is by no means self-evident.

For one, the general public certainly does not think so. They are not blind to the advantages of being able to buy cheap abroad, but worry that at least for the direct victims of cheaper imports, the gains are swamped by the costs. In our survey, 42% of respondents thought that low-skilled workers are hurt when the US trades with China (21% thought that they are helped), and only 30% thought that everyone is helped by the fall in prices (and 27% said that they thought everyone was hurt).

So, is the public simply ignorant, or might it have intuited something the economists have missed?

Stanislas Ulam was a Polish mathematician and physicist, one of the co-inventors of modern thermonuclear weapons. He had a low opinion of economics — perhaps because he underestimated economists’ capacity to blow up the world, albeit in their own way. Ulam challenged Paul Samuelson, our late colleague, and one of the great names in 20th century economics, to “name me one proposition in all of the social sciences which is both true and non-trivial”.

Samuelson came back with the idea of comparative advantage, the central idea in trade theory. “That this idea is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that it is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them.”

Comparative advantage is the idea that countries should do what they are relatively best at doing. To understand how powerful the concept is, it is useful to contrast it to absolute advantage. Absolute advantage is simple: grapes don’t grow in Scotland, and France does not have the peaty soil ideal for making scotch. Therefore, it makes sense that France should export wine to Scotland, and Scotland should export whisky to France. Where it gets confusing is when one country, like China today, looks like it’s pretty much better at producing everything than most other countries. Wouldn’t China simply swamp all markets with its products, leaving other countries with nothing to show for themselves?

Ricardo realised in 1817 that even if China (or, in his era, Portugal) was more productive at everything, it could not possibly sell everything, because then the buyer country would sell nothing and would have no money to buy anything from China. This proved that not all industries in 19th-century England would shrink. It was then evident that if any industry in England were to shrink because of international trade, it should be the ones that were the least productive.

Based on this argument, Ricardo concluded that even if Portugal was more productive than England at producing both wine and cloth, once trade between them opened up, they would nonetheless end up specialising in the product in which they have a comparative advantage (meaning where their productivity is high relative to their productivity in other sector: wine for Portugal, cloth for England). And the fact that both countries make the goods that they are at least relatively good at making and buy the rest, instead of wasting resources producing the latter ineptly, must add to the gross national product (GNP), which is the total value of goods that people in each country can consume.

Ricardo’s insight underlines why there is no way to think of trade without thinking about all the markets together — China could win in any single market and yet, there is no way for it to win in every market.

Of course, the fact that GNP goes up (both in England and in Portugal) does not mean that there are no losers. In fact, one of Paul Samuelson’s most famous papers tells us exactly who they are. Ricardo’s entire discussion had assumed that production required only labour, and all workers were identical, so when the economy became richer, everyone benefited. Once there is capital as well as labour, things are not that simple. But Samuelson, in a paper published in 1941, when he was just 25, set out the ideas that are still the basis of how we are taught to think about it. The logic, once you understand it — as is often the case with the best insights — is compellingly simple.

Some goods require relatively more labour than others to produce and relatively less capital — think of handmade carpets versus robotmade cars. If two countries have access to the same technologies of production for both goods, it should be obvious that the country that is relatively abundant in labour will have a comparative advantage in producing the labour-intensive product, the carpet if you like.

We would therefore expect a labour-rich country to specialise in labour-intensive products and move out of capital-intensive ones. This should raise the demand for labour compared to when there was no trade (or more restricted trade) and therefore wages. And, conversely, in a relatively capital-abundant country, we should expect instead that the price of capital goes up (and wages go down) when it trades with a more labour-abundant partner.

Since the labour-abundant countries tend to be poor, and labourers are usually poorer than their employers, this implies that freeing trade should help the poor in the poorer countries, and inequality should fall there. The opposite would be true in the rich countries. So, opening trade between the US and China should hurt US workers’ wages (and benefit Chinese workers). That does not mean that the workers in the US must necessarily end up worse off. This is because, as Samuelson showed in a later paper, the fact that free trade raises GNP means that there is more to go around for everybody, and therefore, even the workers in the United States can be made better off if society taxes the winners from free trade and distributes that money to the losers. The problem is that this is a big ‘if ’, which leaves workers at the mercy of the political process.

When Trees are Seen as Shady

When a rickshaw-puller in Abhijit’s native Kolkata takes the afternoon off to spend with his lady love, GDP goes down, but how could welfare not be higher? When a tree gets cut down in Nairobi, GDP counts the labour used and the wood produced, but does not deduct the shade and the beauty that are lost. GDP values only those things that are priced and marketed.

This matters because growth is always measured in terms of GDP. 2004, the year when TFP (total factor productivity) growth, after jumpstarting in 1995, slowed down again, is when Facebook began to occupy the outsized role that it currently plays in our lives. Twitter would join in 2006, and Instagram in 2010. What is common to all these platforms is the fact that they are nominally free, cheap to run, and wildly popular. When, as is now done in GDP calculations, we judge the value of watching videos or updating online profiles by the price people pay — which is often zero — or even by what it costs to set up and operate Facebook, we might grossly underestimate its contribution to well-being.

Of course, if you are convinced that waiting anxiously for someone to like your latest post is no fun at all, but you are unable to kick the Facebook habit because all your friends are on it, GDP could also be overestimating well-being.

Either way, the cost of running Facebook, which is how it is counted in GDP, has very little to do with the well-being (or ill-being) that it generates. The fact that the recent slowdown in measured productivity growth coincides with the explosion of social media, poses a problem, because it is entirely conceivable that the gap between what gets counted as GDP and what should be counted in well-being widened exactly at this time. Could it be that there was real productivity growth, in the sense that true well-being increased, but our GDP statistics are missing this entire story ?

यह भी समावेशी सियासत का ही रूप

पूर्वोत्तर में भाजपा की पैठ बढ़ाने में सांस्कृतिक व धार्मिक गतिविधियों को जोड़ने की हिंदुत्व की राजनीति ने बड़ी भूमिका निभाई है।

बद्री नारायण , (लेखक प्रयागराज स्थित गोविंद वल्लभ पंत सामाजिक विज्ञान संस्थान के निदेशक हैं)

असम में गुवाहाटी के पास ब्रह्मपुत्र नदी के किनारे पहाड़ियों की तलहटी में बसे हरे-भरे धान का एक बेहद सुंदर इलाका है, जिसका नाम है म्योंग। स्थानीय भाषा में म्योंग का अर्थ है- माया का लोक। म्योंग क्षेत्र में तमाम गांव बसे हैं। इन गांवों में अनेक हिंदू अपने नाम के साथ ‘गिरि टाइटल या उपनाम लगाते हैं। वे नाथपंथी हैं यानी नाथपंथ में विश्वास करते हैं। कहते हैं कि नाथपंथ के प्रवर्तक गोरखनाथ जी के गुरु मच्छेंद्र नाथ ने यहां आकर इस पंथ का प्रसार किया था। इस क्षेत्र में बसे ये नाथपंथी हिंदू धर्म में विश्वास करते हैं। ये शिव के पूजक हैं। इनमें से अधिकांश चुनावों में भारतीय जनता पार्टी को वोट देते हैं। राजनीतिक रूप से भाजपा के साथ इनका जुड़ाव कोई बहुत पुराना नहीं है। नाथ पंथ के योगी आदित्यनाथ को उत्तर प्रदेश का मुख्यमंत्री बनाए जाने के बाद इन नाथपंथियों का ध्रुवीकरण भाजपा की ओर तेजी से बढ़ा है। इससे पहले ये भाजपा के प्रति इतने अधिक लामबंद नहीं थे।

ऐसे ही कर्नाटक, राजस्थान, मध्य प्रदेश और अरुणाचल प्रदेश जैसे कई राज्यों में नाथपंथी अब भाजपा की ओर उन्मुख हुए हैं। गोरखपुर के आसपास मुस्लिम नाथपंथी जोगी भी हैं। इन जोगियों की बस्ती में भाजपा के प्रति लगाव दिखता है। वहीं उत्तर प्रदेश के अनेक भागों में बसे सपेरे भी नाथपंथ में विश्वास करते हैं। इन सपेरे सामाजिक समूहों में से अधिकांश योगी आदित्यनाथ के उत्तर प्रदेश का मुख्यमंत्री बनने से गौरवान्वित महसूस करते हैं। भाजपा से उनके लगाव की एक वजह यह भी है।

यहां इसका उल्लेख मैं इसलिए कर रहा हूं, ताकि यह स्पष्ट हो सके कि भाजपा ने किस प्रकार हिंदुओं के विभिन्न् वर्गों, धड़ों और मतों को अपने साथ जोड़ा है। अभी तक जब भी भाजपा के पक्ष में राजनीतिक विश्लेषक हिंदू ध्रुवीकरण की बात करते हैं तो ‘सांप्रदायिक ध्रुवीकरण को इसका कारण मानते हैं। यह देखते हैं कि किस प्रकार हिंदुत्व की राजनीति ने हिंदू समाज की विभिन्न् जातियों को जोड़ने के लिए राजनीतिक प्रतिनिधित्व की रणनीति का इस्तेमाल किया है। हम यह नहीं देखते कि किस प्रकार हिंदुत्व की राजनीति ने हिंदू धर्म में सक्रिय अनेक धार्मिक लोकप्रिय पंथों में निहित ‘हेजेमोनी या यूं कहें कि ‘प्रभाव शक्ति का उपयोग उनके समर्थकों को अपने साथ जोड़ने के लिए किया है। पूर्वोत्तर में शंकरदेव के भक्ति पंथ ने तो भाजपा को आधार प्रदान किया ही है। राष्ट्रीय स्वयंसेवक संघ ने हिंदू धर्म जागरण के अभियान के तहत न केवल सनातन पंथों को, वरन अनेक भक्ति पंथों, छोटे-छोटे संप्रदायों और मठों को अपने साथ जोड़कर एक वृहद समग्र हिंदुत्व का वृत्त बनाने की कोशिश की है।

अनेक अखाड़ों, धार्मिक संगठनों की शक्ति का लाभ भारत में हिंदुत्व की राजनीतिक शक्ति को तो मिला ही है मठों, प्रवचन संघों एवं अनेक धार्मिक सामाजिक संगठनों की बुनावट से भाजपा एवं हिंदुत्व की राजनीति को ताकत मिली है। धार्मिक लोकजगत यथा कथा मंडलियों, राम कथा प्रवचक संत संगठनों, भागवत कथा आयोजक संघों एवं संतों तथा हिंदू धर्म की अनेक कीर्तन मंडलियों से निर्मित लोकजगत एक प्रकार से हिंदुत्व की विचार धारा के लोकजगत की शक्ति के रूप में काम करते हैं। तमाम संत, कथा वाचकों को भी समय-समय पर भाजपा स्वयं से जोड़ने के लिए संगठन एवं अपनी राजनीति में जगह देती रही है। उमा भारती, साध्वी प्रज्ञा, साध्वी ऋतंभरा, योगी आदित्यनाथ जैसे अनेक संत कथा वाचक धार्मिक आयोजकों को भाजपा ने अपनी राजनीति में जगह देकर उन्हें एक राजनीतिक मंच उपलब्ध कराया।

अगर बौद्धिक रूप से देखें तो ये कीर्तन मंडलियां, कथा वाचन आयोजक संघ, धार्मिक संस्थाएं हिंदू धर्म की संस्कृति, मूल्यों की चर्चा तो करती ही हैं, राष्ट्र के ज्वलंत मुद्दों को लेकर भी समय-समय पर इनमें विमर्श होता रहता है। ये ज्वलंत मुद्दे राष्ट्र एवं जनतंत्र की राजनीति से भी जुड़े होते हैं। राष्ट्रीय स्वयंसेवक संघ, विश्व हिंदू परिषद, संघ से संबद्ध संगठन, धर्म जागरण मंच ऐसे सार्वजनिक लोकजगत को संयोजित, संगठित एवं जोड़ने का काम करते रहते हैं। प्राय: राजनीतिक विश्लेषक ऐसे धार्मिक लोकजगत की विमर्श रचना एवं राजनीतिक झुकाव पैदा करने में विकसित हो रही इनकी प्रभावी भूमिका को समझ नहीं पाते। भाजपा और संघ से संबंध न रखने वाले लोग आज भी राजनीतिक आधारों के पारंपरिक अर्थ जाति एवं धार्मिक ध्रुवीकरण के सीमित दायरे में ही खोजते हैं। मीडिया कवरेज, राजनीतिक रैली एवं अन्य आयोजनों के अतिरिक्त ये अनौपचारिक रूप से राजनीतिक न होकर राजनीतिक मत सृजित करने वाले सामाजिक, सांस्कृतिक एवं धार्मिक लोकजगत उनकी निगाहों से छूट जाते हैं। किसी राजनीतिक तंत्र की तुलना में ये गैरराजनीतिक लोकजगत भारतीय समाज में राजनीतिक झुकाव पैदा करने में ज्यादा कारगर होते हैं। पश्चिमी समाजों में लोकजगत की अवधारणा से थोड़े भिन्न् भारतीय समाज के ये लोकजगत तर्क से ज्यादा विश्वास की डोर से बंधे होते हैं। तर्कशक्ति से ज्यादा इन समूहों एवं संगठनों के विमर्शों में विश्वास की शक्ति प्रभावी होती है। हिंदू समाज का उच्च वर्ग एवं मध्य वर्ग का एक हिस्सा ऐसे लोकजगत से जुड़ा होता है। साथ ही कबीर पंथ, रविदास पंथ, शिवनारायण पंथ जैसे अनेक लोकप्रिय पंथों के अपने कार्यक्रमों से सृजित लोकजगत के माध्यम से दलित एवं पिछड़ी जातियों का एक बड़ा शिक्षित एवं गैर शिक्षित वर्ग भी इनसे प्रभावित होता है। यह ठीक है कि दलित पंथों से जुड़े पंथों के लोकजगत में हिंदुत्व का विमर्श पहुंचता ही है, साथ ही साथ बहुजन एवं दलित विमर्श में इनके विमर्शों का हिस्सा होता है। कई जगह ये दोनों प्रकार के विमर्श जुड़ जाते हैं तो कई जगह टकराते भी हैं।

दूरदराज व सीमावर्ती प्रांतों में भाजपा का प्रसार मात्र राजनीतिक गतिविधियों या सक्रियता से नहीं हुआ है। इन सामाजिक, सांस्कृतिक एवं धार्मिक पंथों एवं उनके द्वारा सृजित लोकजगत ने भी भारत में हिंदुत्व की राजनीति का सामाजिक आधार तैयार करने में महती भूमिका अदा की है। आज पूर्वोत्तर के राज्यों में भाजपा की जो पैठ बढ़ी है, उसमें राजनीति के साथ सांस्कृतिक एवं धार्मिक गतिविधियों को जोड़ने की हिंदुत्व की राजनीति ने बड़ी भूमिका निभाई है। अब राजनीति ज्यादा चुनौतीपूर्ण होती जा रही है। राजनीति के पारंपरिक अर्थ बदलते जा रहे हैं। जरूरत है राजनीतिक आबद्धीकरण के लिए हो रहे इन नए प्रयासों को समझने की। इनके माध्यम से भारतीय राजनीति के बदलते पक्षों को समझने की जरूरत भी दिन-प्रतिदिन बढ़ती जा रही है।

In His Company

A new report confirms men continue to dominate India Inc. Private sector needs to do more to ensure diversity, equality.

Editorial

If national societies were brands, “diversity” would certainly be the buzzword for India. But so would hierarchy and inequality. The CS Gender 3000 report, released last week by the Credit Suisse Research Institute, is yet another pointer to the woeful lack of equal or even adequate representation of women in the upper echelons of corporate India. According to the report, India’s female representation on corporate boards has increased by 4.3 percentage points over the past five years to 15.2 per cent this year. But this growth is well below the global average of over 20 per cent. India also has the third-lowest rank in the Asia Pacific region with regard to female chief executive officer representation (2 per cent), as well as the second-lowest rank for female chief financial officer representation at just 1 per cent.

The Credit Suisse report merely confirms what has long been known anecdotally: Apart from a few high-profile corporate leaders, by and large, the upper echelons and even senior management positions in the private sector continue to be dominated by men. In fact, at the time of intake, there is far greater gender parity, but the number of women reduces exponentially as we move higher on the pyramid of corporate hierarchy. The report, which surveyed 3,000 companies across 56 countries, also found that, globally, the number of women in leadership has doubled — a fact that makes India’s poor performance all the more stark. The countries that lead the table — Norway, France, Sweden and Italy, for example — either have formal quotas or informal targets for gender parity in place. India’s private sector, though, has long resisted government-imposed quotas for affirmative action.

Since Independence, various attempts have been made to resolve the contradiction between India’s diversity and its inequality, from reservation in government jobs and educational institutions, to the 25 per cent quota for students from economically weaker sections in private schools. The private sector’s resistance to legislation that circumscribes it in matters of hiring and promotion is understandable. Yet, there can be no case for the continuing glass ceiling that women, as well as other marginalised social groups, face, at different levels and in several arenas. Given that the private sector — formal and informal — accounts for over 95 per cent of the labour force, corporate leaders and boards must seriously consider institutionalised mechanisms to ensure diversity and equality. Any case for government regulation is best stymied by proactive action from companies themselves. And, in an era that values innovation and new perspectives in business more than ever before, keeping half the population from roles that could allow them to change the nature of India Inc can only be counterproductive in the long run.

Redirecting money from the Gulf

Kerala has an overdose of mansions and cars; what it needs is investment in job-creating ventures

K.P.M. Basheer, formerly Deputy Editor, The Hindu, is a Kerala-based independent journalist

‘Drop your plan to buy a new car. Avoid eating out. Only buy things you absolutely need. Make do with public transport. Go to government hospitals, not to expensive private ones.’ These were the highlights of a WhatsApp advisory sent out by a Gulf-based organisation two months ago. The advisory targeted the families of non-resident Keralite workers based in the Gulf countries, against the backdrop of the creeping economic slowdown in India. The final advice on the ‘things not to do’ list was that those who were employed in the Gulf countries should never give up their jobs, even if they didn’t get paid on time, “for, there are not many jobs to go around back home because of the economic slowdown.”

The advisory was interesting for two reasons: first, the fact that the diaspora community had sensed, ahead of most people in India, that a slowdown in the Indian economy was imminent; and second, the delayed realisation that non-resident Keralite families must curb certain consumerist habits that were a result of the massive amounts of remittance money they were receiving.

Consumerist economy

A recap of the contours of Kerala’s demographic and economic profile is in order here. Roughly a tenth of Kerala’s 34 million population works abroad — a huge majority of them in the Gulf countries. Kerala’s economy is a consumerist one that has, for decades, been propped up by the massive remittances from non-resident Keralites. Exact numbers are hard to come by, but one estimate is that non-resident Keralites pump close to ₹200 crore daily into the State. Kerala gets roughly a fifth of all NRI remittances to India.

For all its natural resources, impressive literacy and highly evolved State welfare system, Kerala produces very little of its daily needs, including foodgrain and vegetables. Manufacturing contributes less than 10% to the State’s GDP. Agriculture’s contribution is a little above 10%. The unemployment rate is very high. Yet, Kerala’s per capita income is above the national average. Modern mansions can be seen dotting both sides of the road across many parts of Kerala. High-end cars and boutique jewellers’ shops are also common.

This is because of remittance money. Ever since the labour migration to the Gulf started in the 1960s, enormous sums of money have flowed into Kerala. One estimate is that since the beginning of the 21st century, some ₹10 trillion has arrived in the State, including from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman. But almost all this money has gone into consumption and unproductive investments in land, real estate and gold. Why did the non-resident Keralites fritter away their hard-earned money this way, rather than put it into productive ventures? There are many reasons, including systemic rigidities, trade union overkill, lack of imaginative investment avenues, and the absence of a visionary policy framework.

Invest or perish

The WhatsApp advisory might have appeared counterintuitive as macroeconomists say that curtailing consumption will accelerate the slowdown. However, the unstated subtext is that Kerala has enough mansions, cars and jewellery to last another generation. What it lacks is jobs — for residents of the State who are unemployed as well as for non-resident ones who cyclically lose their Gulf jobs and are forced to return home. Had the non-resident Keralites invested even 1% of the massive amount they pumped into Kerala over the past two decades in job-generating ventures, the next generation would have been spared the need to hunt for jobs in the Gulf.