14-09-2020 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here.

Date:14-09-20

Date:14-09-20

Listen to Ribeiro

Police should play a fair and non-partisan role in investigating Delhi riots

TOI Editorials

Julio Ribeiro, iconic police officer who courageously led Punjab police during some of the worst years of the Khalistan militancy, has written to Delhi police commissioner SN Shrivastava demanding a fair probe in the northeast Delhi riots. According to him: “Delhi police has taken action against peaceful protesters, but deliberately failed to register cognisable offences against those who made hate speeches that triggered the riots in NE Delhi.” Delhi police should pay heed to Ribeiro, who battled the fires sparked by Bhindranwale’s hate speeches and almost paid with his life. He must not be cast aside as a political or ideological voice.

Riots recur in India because of the impunity accorded to one section by the political establishment of the day. That has been the sad history of the 1984 Delhi riots, which must not be repeated. Police must clearly distinguish between peaceful anti-CAA protesters and those who actively instigate violence. The latter could fall on either side of the CAA-NRC political divide, and police must strictly follow the evidence in this regard rather than taking sides themselves.

As CPM general secretary Sitaram Yechury said: “It’s my fundamental right and duty to stand up for peaceful protest in defence of constitutional rights.” This democratic right must be permitted, while those actively instigating violence must be hauled up. Questions have been raised, by Ribeiro among many others, why the role of BJP politicians such as Kapil Mishra, Anurag Thakur and Parvesh Verma hasn’t been properly investigated, when some of their statements in the lead-up to the riots have been inflammatory. Proximity to the ruling party shouldn’t be an answer. Ribeiro reminds IPS officers of their vow to uphold the Constitution. This also means not judging citizens by their political or religious beliefs.

The Dog Whistle

Names of Opposition politicians, civil society members, in riot chargesheet criminalises protest, corrodes democracy.

Editorial

The Delhi Police says that neither CPM general secretary Sitaram Yechury nor Swaraj Abhiyan leader Yogendra Yadav, neither economist Jayati Ghosh nor Delhi University professor Apoorvanand, or documentary film-maker Rahul Roy, are named as accused or co-conspirators in a supplementary chargesheet filed in connection with its probe into the February riots in Northeast Delhi. The Delhi Police is right — and wrong. It is true that the two political leaders, two professors and one filmmaker have only been mentioned in disclosure statements, legally inadmissible in court, of three students, facing serious charges for their alleged role in the flaring of the violence. But what is also true, and reprehensible, is the Delhi Police’s dog whistle. This is part of a chargesheet filed in the case of the murder of an 18-year-old, a chargesheet that has glaring discrepancies still to be addressed. So what was the justification of including these names other than the police’s — and its political masters’ — crude attempt at victimising those who expressed their opposition to a discriminatory law by linking them to the violence. The unvarnished message is this: All those who protested against the Citizenship Amendment Act, which, for the first time, makes religion a criterion and excludes Muslims from the list of minorities that are promised fast-tracked citizenship, can be hounded and harassed by a police force with a political view. A police that is now trampling over vital distinctions in a democracy, and equating the protester with the rioter. One that is acting — and being seen to act — as a force that will not stop at weaponising laws to criminalise the dissenter.

The investigation of the Delhi Police into the violence in Northeast has started with a conclusion — that a conspiracy was afoot to defame and destabilise the elected government, and that it included and involved those who were protesting at the time against Muslim exclusion and relegation in the CAA and proposed nation-wide NRC. It matters little, in this narrative, what the facts are — the victims of the violence were those whom it seeks to cast in the role of perpetrators, the brunt was borne by the Muslims. It matters little, too, whether the police is eventually able to find the evidence — it won’t, against individuals with as impeccable and distinguished credentials in public life as Yechury or Yadav. But in the meantime, it can unleash the due process as punishment. And send out a chilling signal, not just to Muslims, but to all those who speak for a more inclusive India, that they can speak freely, and criticise the government openly, at their own peril.

The Delhi riots case is fast becoming a pivotal test for the Delhi Police. It needs to shine the light on the complicities within. Last week, as this newspaper reported, the Delhi Police Crime Branch questioned a policeman posted with the Delhi Armed Police while investigating the death of 24-year-old Faizan, after he, along with two other men, was allegedly made to sing the national anthem and Vande Mataram by a group of policemen. But this is only a small first step. It must remember that at stake is its endangered credibility as a professional force in a country where — and here is a distinction that will not and cannot be obliterated — there is rule of law, not merely rule by law.

Date:14-09-20

Diminishing Parliament

Cancelling Question Hour erodes constitutional mandate of parliamentary oversight over executive action

P Rajeev, [ The writer, a former Rajya Sabha MP, is a senior CPM leader]

The decision to go without “Question Hour” during the Monsoon Session of Parliament, beginning September 14, has evoked serious concerns about the democratic functioning of the institution. Question Hour is not only an opportunity for the members to raise questions, but it is a parliamentary device primarily meant for exercising legislative control over executive actions. It is also a device to criticise government policies and programmes, ventilate public grievances, expose the government’s lapses, extract promises from ministers, and thereby, ensure accountability and transparency in governance.

The annals of history of parliamentary proceedings and functioning in India remind us of the strength and scope of Question Hour as an effective armour to raise the concerns of the people. A classic illustration of this role can be gleaned from this exchange in the Lok Sabha in November 1957.

Ram Subhag Singh (Congress): “Whether LIC had purchased large blocks of shares from different companies owned by Mundhra?”

Deputy Minister of Finance: “Towards the end of June 1957, the corporation had invested Rs 1,26,86,100 in concerns in which Shri HD Mundhra is said to have an interest.”

Supplementary question by Feroze Gandhi (Congress): “May I know whether it is a fact that a few months ago shares were purchased at the higher price than the market of those very shares on that particular day.”

T T Krishnamachari (Union Minister for Finance): “I have been told that no such thing has happened.”

These words soon came to haunt the minister himself and cost him his job in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Cabinet. Dissatisfied with the minister’s reply, Feroze Gandhi initiated a half-an-hour discussion on the subject. This single instance points out the poignant relevance of the half-an-hour discussion and the contributing character of Question Hour in the proceedings.

In the discussion, Feroze Gandhi unfolded the story of murky deals involving LIC. The government was forced to appoint a commission of enquiry headed by Justice M C Chagla. Feroze Gandhi promptly offered to be a witness and was the first to testify. Justice Chagla upheld Feroze Gandhi’s contentions and said that the finance minister should take moral responsibility for what had happened. Krishnamachari resigned. This incident shows the strength and scope of the Question Hour.

The Narendra Modi government is in dire need to avoid these type of situations. The time has come to grill this government on different issues such as its failure in handling the pandemic, the unprecedented decline in GDP and its impact on the economy, the New Education Policy, tensions at the border, rising unemployment, the miseries of migrant labour and so forth. The government is duty bound to respond to these questions in Parliament. By doing away with the Question Hour, the Modi government has opted for a face-saving measure.

The right to question the executive has been exercised by members of the House from the colonial period. The first Legislative Council in British India under the Charter Act, 1853, showed some degree of independence by giving members the power to ask questions to the executive. Later, the Indian Council Act of 1861 allowed members to elicit information by means of questions. However, it was the Indian Council Act, 1892, which formulated the rules for asking questions including short notice questions. The next stage of the development of procedures related to questions came up with the framing of rules under the Indian Council Act, 1909, which incorporated provisions for asking supplementary questions by members. The Montague-Chelmsford reforms brought forth a significant change in 1919 by incorporating a rule that the first hour of every meeting was earmarked for questions. Parliament has continued this tradition. In 1921, there was another change. The question on which a member desired to have an oral answer, was distinguished by him with an asterisk, a star. This marked the beginning of starred questions.

These are democratic rights members of Parliament have enjoyed even under the colonial rule. The sad part is that this right is being denied to the elected representatives of Independent India, by the present government. This, however, is not an isolated action in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. For instance, the government passed important bills in the first session of the 17th Lok Sabha before the formation of department-related standing committees. Even the Constitution Amendment Bill on J&K was introduced without circulating copies to the members. Several important bills were passed as Finance Bills to avoid scrutiny of the Rajya Sabha. Standing committees are an extension of Parliament. Any person has the right to present his/her opinion to a Bill during the process of consideration.

The government’s actions erode the constitutional mandate of parliamentary oversight over executive actions as envisaged under Article 75 (3) of the Indian Constitution. Moreover, such actions prevent the members of Parliament from carrying out their constitutional obligations of questioning, debating, discussing and scrutinising government policies and actions. It needs to be understood that these actions are a planned covert attempt by the government to diminish the role of Parliament and turn itself into an “Executive Parliament”.

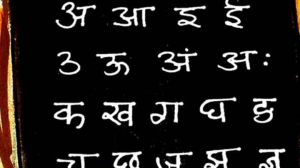

हिंदी कब बनेगी न्याय की भाषा

प्रो. रजनीश कुमार शुक्ला ( लेखक महात्मा गांधी अंतरराष्ट्रीय हिंदी विश्वविद्यालय, वर्धा के कुलपति हैं )

राजभाषा पर संसदीय समिति ने 28 नवंबर, 1958 को संस्तुति की थी कि सर्वोच्च तथा उच्च न्यायालयों में कार्यवाही की भाषा हिंदी होनी चाहिए। इस संस्तुति को पर्याप्त समय बीत गया, किंतु इस दिशा में अब तक कोई सार्थक प्रगति नहीं हुई, जबकि भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 348 की धारा-दो के अनुसार किसी भी प्रदेश के राज्यपाल राष्ट्रपति की सहमति से हिंदी या उस प्रदेश की राजभाषा में उच्च न्यायालय की कार्यवाही संपादित करने की अनुमति दे सकते हैं। इसी अनुच्छेद का लाभ लेते हुए राजस्थान, मध्य प्रदेश, उत्तर प्रदेश और बिहार के उच्च न्यायालयों में अंग्रेजी के साथ-साथ हिंदी में भी कार्यवाही की अनुमति दी गई है, परंतु इसी तरह की मांग जब अन्य राज्यों से की गई तो उनकी मांग को ठुकरा दिया गया। 2008 में विधि आयोग को सर्वोच्च न्यायालय और उच्च न्यायालयों में हिंदी में कामकाज की संभावना पर अपनी संस्तुति देने का कार्य सौंपा गया, किंतु उसने नकारात्मक रिपोर्ट दी और उच्चतर न्यायपालिका में हिंदी सहित भारतीय भाषाओं के प्रवेश पर एक बार फिर प्रतिबंध लग गया। 27 जुलाई, 2009 को संसद में विधि आयोग के 216 वें प्रतिवेदन के संबंध में जानकारी देते हुए तत्कालीन विधि एवं न्याय मंत्री वीरप्पा मोइली का वक्तव्य था कि आयोग ने हिंदी को सर्वोच्च न्यायालय एवं उच्च न्यायालयों के कामकाज के लिए अव्यावहारिक बताया है। इसके पीछे राजनीति तो थी ही, भारतीय विधि शिक्षा का अभारतीय स्वरूप भी एक महत्वपूर्ण कारण था। इससे बड़ी विडंबना और कोई नहीं कि हिंदी को संयुक्त राष्ट्र की आधिकारिक भाषा बनाने की बात तो होती है, परंतु देश में उच्चतर न्यायपालिका की भाषा हिंदी हो, इस पर लोग मौन हैं।

शिक्षा के भारतीयकरण के अभियान को नई शिक्षा नीति 2020 के द्वारा सफलता प्राप्त हुई है, लेकिन उच्चतर न्यायपालिका में भारतीय भाषाओं के प्रतिबंध को लेकर कहीं कोई बहस नहीं हो रही है। भारत की स्वतंत्रता के 73 वर्ष और हिंदी को राजभाषा के रूप में स्वीकृति के 71 वर्ष पूर्ण होने के बाद भी देश की न्याय व्यवस्था नागरिकों को स्वभाषा में न्याय नहीं उपलब्ध करा सकी है। न्याय व्यवस्था का प्रश्न मात्र भाषा का नहीं है। स्वयं न्याय की अवधारणा, विधि का विवेचन और उसके न्यायानुकूल होने का प्रश्न भी महत्वपूर्ण है। न्याय व्यवस्था का आधार विधिशास्त्र है। विधि का लेखन जिस भाषा में होता है, वह साधारण भाषा है। प्रत्येक साधारण भाषा स्वाभाविक रूप से अपने परिवेश के आधार पर ही अर्थ संस्थान का निर्माण करती है। अनूदित विधि हमेशा अर्थ बोध के लिए मूल भाषा की मुखापेक्षी होती है। सर्वोच्च न्यायालय तथा उच्च न्यायालयों का मुख्य कार्य विधि को संविधान एवं प्राकृतिक न्याय के आलोक में व्याख्यायित करने का है, साथ ही अवर न्यायालयों के निर्णयों का न्यायिक पुनरीक्षण भी करना है। ये दोनों कार्य भाषाई विश्लेषण पर आधारित निर्वचन प्रणाली की अपेक्षा करते हैं। यह कार्य किसी भी विधिक पाठ अथवा संविधि की व्याख्या से जुड़ा हुआ कार्य है। अत: इसमें किसी भी विधि पाठ का अर्थ बोध सुनिश्चित करना अपेक्षित होता है। अभी तक भारत में विधि के निर्वचन के लिए जिस सिद्धांत का प्रयोग होता है, वह मैक्सवेल का ‘ऑन दी इंटरप्रिटेशन ऑफ स्टेट्यूट्स’ नामक ग्रंथ है। यह किताब लंबे काल से ब्रिटिश विधि के क्षेत्र में व्याख्या की बाइबिल समझी जाती है। यह किताब स्वयं में कोई विधि नहीं है, अपितु विधिशास्त्र की एक ऐसी किताब है, जो परंपरा द्वारा विधि की प्रमाणिक व्याख्या प्रणाली के रूप में स्वीकृत हो गई है। यह सच है कि हिंदी भाषा में इस तरह की प्रणाली का विकास नहीं हुआ है। अत: सर्वोच्च न्यायालय तथा उच्च न्यायालयों के हिंदी में कामकाज में कठिनाई स्वाभाविक है। यदि हिंदी और अन्य भारतीय भाषाओं को वास्तविक रूप से न्यायिक कामकाज की भाषा बनाना है तो संविधि की व्याख्या का सिद्धांत तैयार करना होगा। यह कार्य अनुवाद से संभव नहीं है।

मैक्सवेल की निर्वचन प्रणाली ब्रिटिश विधि व्यवस्था और उसके परंपरागत विधिशास्त्र पर आधारित है। भारतीय संदर्भ उसमें नहीं हैं। यही कारण है कि जटिल विषयों पर प्रस्तुत निर्णय समस्त शास्त्रीय शुद्धता के बाद भी आमजन को चौंकाने वाले हो जाते हैं। न्यायालयों में हिंदी के साथ-साथ अन्य भारतीय भाषाओं के प्रयोग को संभव बनाने का एकमात्र तरीका है कि मैक्सवेल को अपदस्थ किया जाए एवं भारतीय प्रणाली, संस्कृति को प्रकट करने वाली व्याख्या विधि को स्थापित किया जाए। स्वाभाविक तौर पर इसके लिए भारतीय इतिहास की ओर झांकना होगा। 1857 से भारतीय विधि के इतिहास और विकास को समझने के स्थान पर विधिशास्त्र के संपूर्ण भारतीय इतिहास को समझना होगा, जो 1857 के पूर्व से प्रारंभ होता है। ऐसी स्थिति में हमारा ध्यान स्वाभाविक रूप से मीमांसा की निर्वचन विधि की ओर जाएगा, जो विधि सहित विविध शास्त्रों की व्याख्या प्रणाली के रूप में सहस्नों वर्षों से भारत में स्वीकृत रही है। इसमें अनुभव आश्रित एक ऐसी विशिष्ट गतिशीलता है, जो इसे मैक्सवेल की अपेक्षा अधिक उपयोगी और वस्तुनिष्ठ बनाती है। भारत में पुरातन काल से ही इसका प्रयोग होता रहा है। 20वीं और 21वीं शताब्दी में भी इस दिशा में अनेक कार्य हुए हैं। यदि ये कार्य हिंदी सहित अन्य भारतीय भाषाओं में हुए होते तो इसके आधार पर व्याख्या की एक ऐसी प्रणाली का विकास किया जा सकता था, जो मैक्सवेल को खारिज कर सकता था, किंतु इस दिशा में कार्य करने वाले सभी विद्वानों ने भाषा के महत्व की ओर ध्यान नहीं दिया। मैकाले को नकार कर भारतोचित शिक्षा की आवश्यकता को नई शिक्षा नीति 2020 पूर्ण करती है। अब न्याय की पश्चिमी प्रणाली को नकारने के लिए मैक्सवेल को भी खारिज करना होगा।

![]() Date:14-09-20

Date:14-09-20

सर्वोच्च न्यायालय इस खाली समय में तलाशे नए समाधान

एम जे एंटनी

कोरोनावायरस के कारण न्यायालयों में बहुत कम मामलों की सुनवाई हो रही है। बहुत से न्यायाधीश अच्छी वीडियो कॉन्फ्रेंसिंग सुविधाएं न होने और डिजिटल कौशल के अभाव के कारण लंबे समय से अटके मामलों को निपटा नहीं पा रहे हैं। सर्वोच्च न्यायालय में एक-तिहाई न्यायाधीश किसी समय विशेष पर मामलों की सुनवाई नहीं कर रहे हैं। इस खाली समय का इस्तेमाल बड़ी तादाद में लंबित मामलों और महामारी के कम होने पर नए मामलों की बाढ़ आने के आसार जैसी न्यायपालिका की समस्याओं के अदालत के स्तर पर ही समाधान खोजने में किया जा सकता है। लेकिन लॉकडाउन के इन पांच महीनों में शीर्ष कानूनविदों ने इन पर विचार-विमर्श करने के लिए समय नहीं दिया। आगे भी कुछ ऐसे अनुत्पादक महीने बीतने के आसार हैं, जो लंबित मामलों की तादाद के आंकड़े जुटाने और उनका विश्लेषण करने के लिए पर्याप्त मौका दे रहे हैं। ताकि अदालती प्रणाली में मामलों का अंबार लगाने वाली प्रक्रियाओं और परंपराओं की समीक्षा जैसे समाधान तलाशे जा सकें।

हालांकि सर्वोच्च न्यायालय को संवैधानिक अदालत माना जाता है। लेकिन संविधान से जुड़े मामलों की संख्या संपत्ति मालिक-किरायेदार विवाद, सेवाओं में पदोन्नति या परिवार की संपत्ति के बंटवारे आदि से संबंधित आम मामलों की तुलना में बहुत कम है। पिछले साल तत्कालीन मुख्य न्यायाधीश रंजन गोगोई ने एनरॉन-दाभोल भ्रष्टाचार मामले में समाधान का एक रास्ता दिखाया था। उन्होंने 17 साल पुराना मामला होने की वजह से इस पर ध्यान देना बंद किया। किसी ने शिकायत नहीं की। वह जानते थे कि समय जनता की याददाश्त से किसी भी निशान को मिटा सकता है।

सर्वोच्च न्यायालय की वेबसाइट के मुताबिक 19,492 मामले अंतिम सुनवाई के लिए तैयार हैं, जिनमें से बहुत से दो दशक से भी अधिक पुराने हैं। हालांकि देश एक आर्थिक संकट से जूझ रहा है, लेकिन ऐसे कर विवादों की संख्या आश्चर्यजनक है। उनमें प्रत्यक्ष कर याचिकाएं 2,431 हैं, जबकि अप्रत्यक्ष कर की याचिकाओं की संख्या 2,288 है। सबसे पहले की प्रत्यक्ष कर याचिका वर्ष 1992 की है। यह संभव है कि इन मामलों में विवाद की शुरुआत कम से कम एक दशक पहले न्यायाधिकरण, अपील निकाय और फिर उच्च न्यायालय से शुरू हुई होगी।

बीते दशकों के दौरान कर कानूनों में बड़ा बदलाव आया है, जिससे कानूनी मुद्दे अप्रासंगिक बन गए हैं। यह भी संभव है कि करदाताओं की अभियोग में रुचि न रही हो या वे खुद ही न रहे हों।

प्रत्यक्ष कर पर सीएजी की रिपोर्ट (2017-18) के मुताबिक विभिन्न अदालतों में 82,643 मामले लंबित थे, जिनमें 4,42,825 करोड़ रुपये फंसे हुए थे। इनमें से 6,224 मामले सर्वोच्च न्यायालय में अटके हैं, जिनमें 11,773 करोड़ रुपये की राशि फंसी हुई है। वहीं 39,066 मामले उच्च न्यायालयों में लंबित हैं, जिनमें 196 लाख करोड़ रुपये फंसे हुए हैं। राजस्व विभाग के अपनी याचिकाओं में जीत हासिल करने के आसार बहुत कम हैं। वर्ष 2017-18 की आर्थिक समीक्षा में दर्शाया गया है कि अथॉरिटी प्रत्यक्ष कर के 87 फीसदी मामले हार गईं, जिसमें 73 फीसदी मामले अकेले सर्वोच्च न्यायालय में हारे। इन मामलों से करदाताओं का समय और पैसा जुुड़ा होता है, इसलिए इन मामलों को जल्द से जल्द चयनित और खत्म किया जाना चाहिए। इन विभिन्न प्रकार के आर्थिक मामलों के अलावा ऐसे बहुत से संवैधानिक सवाल हैं, जो बड़े पीठों द्वारा अंतिम सुनवाई के लिए तैयार हैं। इनमें 90 याचिकाओं की सुनवाई नौ सदस्यीय पीठ करेगा, 12 मामलों की सात सदस्यीय पीठ, 113 मामलों की पांच सदस्यीय पीठ और 376 मामलों की तीन सदस्यीय पीठ सुनवाई करेगा।

मुख्य न्यायाधीश को निपटाने के लिए मामलों को चुनने, उनके समय और उनकी सुनवाई के लिए न्यायाधीशों के नाम तय करने का प्रशासनिक अधिकार मिला हुआ है। वर्चुअल अदालत आगे भी बरकरार रहेंगी, इसलिए बहुत से पुराने मामलों को उन्हें सौंपा जा सकता है। आगामी दिनों में मुख्य न्यायाधीश के लिए प्रमुख नीतिगत फैसला उन मामलों को अलग करना होगा, जो फिजिकल और वर्चुअल अदालतों के समक्ष जाएंगे। इस गंभीर स्थिति को देखते हुए उन मामलों को वरीयता दी जानी चाहिए, जिनसे कानून का बड़ा सवाल जुड़ा है। सैकड़ों पुराने लंबित मामलों पर गोगोई जैसा प्रहार कर उन्हें स्मृति के दायरे में भेजा जा सकता है। बहुत से वादियों को अपने दावों पर समझौता करने और अपनी नियति पर झुकने को लेकर कोई एतराज नहीं होने की संभावना है।

एक अन्य संबंधित कदम मामलों को सूचीबद्ध करने के दिशानिर्देश बनाना है। अगर कुछ निश्चित पारदर्शी नियम होते तो हाल में न्यायालय की आलोचना को टाला जा सकता था। जो न्यायाधीश सेवानिवृत्ति के कगार पर हैं, उन्हें महत्त्वपूर्ण मामले नहीं दिए जाने चाहिए। उदाहरण के लिए केशवानंद भारती मामले में इंदिरा गांधी मूलभूत अधिकारों पर पहले के फैसले को जल्द से जल्द पलटवाना चाहती थीं। बाद में बहुत से लेखकों ने पर्दे के पीछे उनकी अनैतिक गतिविधियों को ग्राफिक के हिसाब से दर्ज किया है, जिनमें आसानी से प्रभावित होने वाले न्यायाधीश भी शामिल थे। अयोध्या मामला सबसे बड़े विवादित मामलों में से एक है, जिस पर मुख्य न्यायाधीश की अदालत में वकीलों ने जिरह की। इसमें यह पेच था कि इसकी सुनवाई 2019 के आम चुनावों से पहले हो या बाद में। अगर मामलों की सूचीबद्धता के ठीक से परिभाषित मापदंड, माना कि कालक्रमानुसार होंगे तो सुनवाई के समय को लेकर विवाद की कोई जरूरत नहीं होगी। दुर्भाग्य से सभी मुख्य न्यायाधीश एक भरोसेमंद प्रणाली विकसित करने से बचे हैं। शायद इसकी वजह यह हो कि उनके हाथ में अप्रतिबंधित विवेकाधीन शक्तियां हों। या वे अल्प कार्यकाल की वजह से पंगु हों, जिसने उन्हें ऐसे समय दीर्घकालिक समाधान के लिए हतोत्साहित किया हो, जब वे अपने खुद के भविष्य के बारे में सोच रहे हों। इसलिए अब बदलाव की पहल बार की तरफ से होनी चाहिए, जो बराबर का भागीदार है।