14-08-2023 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here.

Date:14-08-23

Date:14-08-23

Small With Smarts

Affordable innovations with demonstrable public utility should be one of India’s R&D priorities.

TOI Editorials

As the season in which NCR and other parts of north India see AQI rise past 400 approaches, every headline that gives hope that this year shall be different is being read with bated breath. One promising development is that around half of Punjab’s paddy cultivation area has been sown with the short-duration variety, PR-126. Punjab Agricultural University had released it in 2017, but this year it got a big boost from the heavy rains. The calculation is that because it matures early and produces less stubble, this paddy variety will lower air pollution. In other good news, a startup mentored by IIT-Delhi has tested a device that reduced PM2.5 and PM10 in its reach area by up to 86% within two hours in the pilot project.

While there have been many false dawns in the fight against air pollution, this device has been validated by the atmospheric science department of IIT-Delhi. It ionises the air to make particle pollutants heavier, thus removing them from the air and stopping the spread of pollution. It holds a low-cost promise for traffic junctions and other hotspots.

The Anusandhan National Research Foundation (NRF) Bill, 2023 passed by Parliament this month, is about seriously hiking R&D spend in the country. This is critical to becoming truly globally competitive, instead of remaining disproportionately dependent on imported technologies. But the air pollution story is a reminder that there is a wide, wide world beyond big-ticket R&D. There are problems awaiting affordable solutions across so many different sectors, which can be delivered by nimble startups, with the right access to capital and mentorships. IITs have been the workhorses of startup incubation. But plans like that of the IIT-Madras incubation cell to take this game to tier-2 and tier-3 cities are very important. Because widening the pool of ideas widens the odds of a successful innovation.

Not every entrepreneurial claim stands up to real-life testing. This is part of the innovation adventure and it’s absolutely ok, as long as the peer review processes are timely and robust. Consider the importance of low-cost stents and ventilators and water purifiers in health or affordable electric scooters in transport. New efforts are reported everyday and perhaps they are underway in every sector. But these still remain too few, compared to the scale of Indians’ needs – and, crucially, potential.

Date:14-08-23

Curing Medicine

NMC’s new rules on doctors include social media code of conduct & pharma sponsors. Enforcement may be tricky.

TOI Editorials

In another first NMC has made compulsory the existing requirement for “continuous professional development” throughout a doctor’s working years, and amusingly, has specified that none of the conferences or seminars that may count as CPD can be sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. It will be interesting to watch how this plays out. Pharmaceutical companies and diagnostics chains are in a cosy, seemingly unbreakable relationship with hospitals and doctors. CPD for doctors is driven by pharma sponsorship. If they don’t fund seminars, who will? That’s the question.

New regulations reiterate that doctors must prescribe generic medicines. A good idea that has to deal with wide quality variations among generics. GOI must address issues with generics sold in the open market. When a prescribed generic is not available, it is often the pharmacist who suggests the substitute. GOI’s chain Jan Aushadhi shops are often poorly stocked though India’s generics sector ranks among the top in the world. How effectively NMC’s regulations will pan out will thus depend on the penalties, which are yet to be framed.

Date:14-08-23

Some I-Day Musings

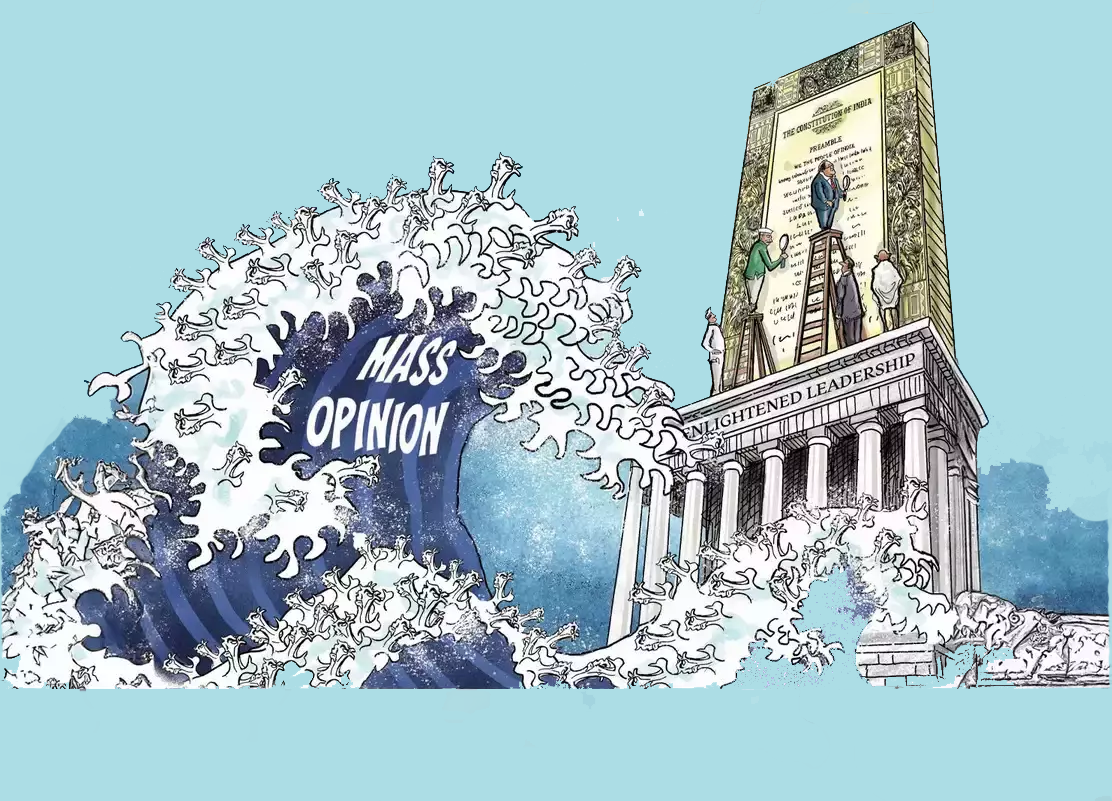

Courage and expert thinking went into crafting India’s forward-looking Constitution, which would have lost many of its admirable features had a referendum of mass opinion been held.

Dipankar Gupta, [ The writer is a sociologist. ]

In 1945, Congress indeed demanded Independence, but it was not a single point thrust as it is with most referendums. There was a clear promise here to also fight against casteism and for the rights of minorities and women, which required more than a tick on the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ box. The Tryst with Destiny speech too indicated that there were pledges yet to be fulfilled.

In contrast to most national movements, not just those of Pakistan and Bangladesh, but also Indonesia and Malaysia, our Independence heroes had Constitution making on their minds. Such a Constitution had to be full bodied, in order to fulfil the ‘tryst with destiny’ promises. This required expert thinking by extraordinary people; it could not be a mass affair.

This is why our Constitution makes no room for referendums for, if it did, many of the forward-looking provisions in it would have been diluted even before the ink went dry. Rajendra Prasad, for example, turned down the proposal for a referendum on national language and saved the country from a Sri Lanka-like civil war.

Had the founders of our Constitution fainted in embarrassment at mass opinion, we might have been deprived of laws against untouchability and for safeguarding minorities. Even the Hindu Marriage Act, would have, in all likelihood, been massacred if it had been put to a referendum-like ballot. Mass opinion needs discipline and homework; it cannot run loose.

Babasaheb Ambedkar had made a prescient, and no-nonsense observation, that democracy in India was still a “top dressing” on Indian soil. This is why “constitutional morality” along with “fraternity” requires patient nurturing to take off. Under these conditions, if referendums happened, our Constitution would have lost some of its most admirable features.

It needed the Mahatma’s fortitude to uncompromisingly fight against untouchability even when some of his own family members disagreed with him. Popular opinion and referendum could have killed it. Democracy requires enlightened leadership for it is delicate and precious. The slightest concession to crude electoral pressure can hurt, often fatally.

When our Independence Day gave notice that a Constitution was not far behind, it demonstrated how multifaceted and thoughtful our struggle to be free has been. That it took several years, from 1946 to 1950, to finalise this document is evidence of the long hours of thinking and contemplation that went into it. It wasn’t fired off as a single salvo.

At first sight, referendum, like violence, seems easier; the snares show up much later. It took courage for our leaders to actually fight popular opinion of the day to craft our Constitution. It is this commitment to citizenship values that prompted them to position “fraternity” in our Constitution’s opening sentence; a remarkable feat, especially for a caste-ridden society.

A referendum may look smart but to get into its tight outfit one has to unhook citizenship of its ribcage and place most of its vital organs in deep freeze. Democratic leaders who look at the long term and not for instant popularity have to invariably go against the mood of the day and what the majority may think is svelte and good looking.

Or else, there is the danger of going through the phase Malaysia once experienced with its Malayan-first policy. Closer home, indifference to citizenship led to Pakistan’s dismemberment and the bloody years of Sri Lanka’s civil war. When leaders of our Independence movement often had to go against popular beliefs they were not alone in this.

The history of democracy shows that almost all major democratic advances even in the West, happened because leaders had the courage and gumption to challenge popular opinion. From the introduction of universal health and education to anti-child labour laws, to women’s suffragette, and old age pension, elite leadership not mass pressure led the charge.

This line of thought has an illustrious genealogy of thinkers. From Jean Jacques Rousseau to Joseph Schumpeter, to Babasaheb Ambedkar to the judges of the Kesavnanda Bharati case, there is a clear distaste of mass pressures. After all, it was such populist polls that brought about Hitler, stymied the peace deal in Colombia and sealed the deal on Brexit too.

It may well be argued that greater the participation, the weaker the governance but this is just one side of the issue. What our Independence leaders, who were also our Constitution founders, demonstrated was that it needed dexterous helmsmanship from above if the country is not to become a sink of communalism and casteism – of the kind Ambedkar feared.

In the fitness of things, on Independence Day, we must once again salute the citizenship-inspired leaders who gave us both freedom and the Constitution. They had the courage and conviction to go against the tide, and often against their self-interests too. Without them, India would have been yet another bigoted country, like so many others in the world today.

Not surprising then that Rabindranath Tagore’s Ekla Cholo Re should be one of Gandhi’s favourite songs. It was quite in character with the Mahatma to walk long miles alone.

Date:14-08-23

Criminal Law: Too Much Of The Old In The New

How much does the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bill depart from Macaulay’s IPC? Too little. It continues to rely on harsh punishments and vaguely defined offences.

Naveed Mehmood Ahmad, [ The writer is a Senior Resident Fellow, Criminal Justice at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. ]

Three new bills seek to replace the colonial-era IPC, CrPC and the Indian Evidence Act. Their declared aim is to transform India’s criminal justice system, eliminate “the signs of slavery”, and ensure justice rather than punishment. Here we unpack the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bill, 2023 that is set to replace IPC.

Why does IPC need replacing?

Enacted in 1860, IPC is a comprehensive penal code. Over the years, other criminal laws have followed its scheme and conceptual basis. The new bill seeks to replace IPC to serve the contemporary needs better, plus to create a citizen-centric legal structure. Specific changes include recognising community service as a form of punishment, making offences gender neutral, dealing with organised crimes and terrorism, and adding new offences relating to secession and armed rebellion.

In the new bill, which offences attract community service?

The bill recognises community service as a form of punishment and prescribes it for at least six offences – a public servant unlawfully engaging in trade, nonappearance in response to a proclamation, attempt to commit suicide to compel or restrain exercise of lawful power, theft of low-value goods, public misconduct by a drunk, and defamation. Strangely, the bill does not explain what kind of work may constitute community service. This lack of clarity may lead to imposition of arbitrary and inappropriate punishments.

Which offences have been made gender neutral?

The bill redefines the offences of ‘Voyeurism’ and ‘Assault to disrobe a woman’. While under IPC only men can be charged for these offences, ‘any person’ can be charged under the new bill. The offences of rape, sexual harassment and stalking continue to be gender specific. Interestingly, the provisions have been made gender neutral only in case of the offender.

Victims can only be women. This is unlike POCSO Act, 2012, where both offender and victim can be of any gender.

How have the reins on organised crime & terrorism been tightened?

The bill provides a comprehensive definition for ‘Organised Crime’ – including the offences of kidnapping, robbery, trafficking, and other economic and cyber crimes, when committed by a group of individuals, whether as members of a crime syndicate or for such a syndicate.

Being a member of an organised crime syndicate or attempting, committing, conspiring and assisting in organised crime may lead to a mandatory minimum imprisonment for five years or life imprisonment. An organised crime leading to the death of any person may be punished with death or life imprisonment.

Similarly, terrorist acts have been defined as acts that disturb public order; intimidate the general public; or threaten the unity, integrity and security of India. Commission of such acts, either by use of explosives, or by destroying property or critical infrastructure etc can attract a minimum imprisonment of five years, life imprisonment and even death in some cases.

Is sedition repealed or reinforced?

The bill omits the offence of sedition by name, which currently criminalises inciting disaffection or hatred against the government. However, a new offence has been added that criminalises exciting secession, armed rebellion, subversive activities or encouraging separatist feelings. Committing any such act may attract life imprisonment.

The framing of this provision has a striking resemblance to that of sedition. It continues to criminalise ambiguous acts of ‘exciting secession’ and ‘encouraging separatist feelings’, without defining subversive, secessionist and separatist activities. With both the criminalised acts and the subjects of protection – sovereignty, unity and integrity of India – still vague the new provision is perhaps more insidious than sedition.

What are the big misses?

Projected as a means to shed the colonial legacy, the bill actually does little in this direction. Macaulay’s IPC was based on the idea that punishments inspire terror and thereby prevent crime. The new bill reinforces this idea by continuing to rely on long-term imprisonments and the death penalty, by adding and increasing mandatory minimum sentences for certain offences, and by retaining vague definitions for offences against the state as well as for defamation.

Even though the bill was introduced on the plank that offences against women will be given precedence, it continues the indifference towards marital rape.

If the idea is to transform India’s criminal laws, clinging to the past will not help. A fresh look at the object of criminal law in the Indian context and a principled approach towards criminalisation and punishments will go a long way in Indianising the criminal justice system.

Rebooting the codes

Criminal laws may need reform, but not new and unfamiliar names.

Editorial

Few would disagree that laws require an overhaul from time to time so that they could be abreast of developments in technology and changes in society. However, it does not mean that whole new Codes be introduced and given abstruse names, when, in substance, the old laws are essentially retained. The first criticism about the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS, to replace the Indian Penal Code), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS, to replace the Code of Criminal Procedure) and the Bharatiya Sakshya Bill (to replace the Indian Evidence Act) is that it is unnecessary to refer to them wholly in their Hindi names. Every law in India has an official translation in the respective official language of every State; so the need for the IPC, CrPC and Evidence Act to be referred to in their Hindi names alone is questionable. The criminal procedure law was re-enacted in 1973, and it is known as the CrPC, 1973, as distinct from its 1898 version. The objective to have Hindi names is apparently an attempt to symbolise the de-anglicisation of criminal law. However, a preliminary scroll through the new laws indicates that much of the original language is retained. It raises a doubt whether the changes are far too few to warrant their being enacted afresh, as deletions and amendments may have achieved the same purpose. It is some consolation that the ‘Sanhitas’ are to be scrutinised by a Parliamentary Standing Committee, as the consultation process appears inadequate.

In substance, the deletion of ‘sedition’ is welcome, and its apparent equivalent, the new Section 150, does not use overbroad terms such as promoting ‘disaffection’ against the government or bringing it into ‘hatred or contempt’. It criminalises promoting secessionism, separatism and armed rebellion, but it also targets ‘subversive activities’ and ‘endangering the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India’ — terms that should not be allowed to be misused. Another potentially misusable provision is in the new Section 195 (equivalent to Section 153B IPC): it penalises making or publishing “false or misleading information jeopardising the sovereignty, unity and integrity or security of India”. While ‘mob lynching’ and ‘organised crime’ are new sections, a significant omission is ‘hate speech’ even though defining it and punishing it have been under discussion for some years. The procedure code enables conduct of trial of proclaimed offenders in absentia. Making videography of seizures mandatory is welcome. So too the provision for deemed sanction if authorities fail to grant it within 120 days. However, the remand provisions seem to permit police custody beyond the current 15-day limit, attracting some criticism. The new laws need critical scrutiny, but not new names.

Date:14-08-23

Glaring omission

Govt. should have stayed true to top court judgment on ECI selection process.

Editorial

The Union government’s proposal to have a three-member selection panel with a majority for the executive for the appointment of members of the Election Commission may not subserve the objective of protecting the poll watchdog’s independence. A Bill introduced in the Rajya Sabha says the committee will consist of the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition and a Union Cabinet Minister. This runs counter to a recent judgment of a Constitution Bench that envisaged an independent selection committee that included the Chief Justice of India. The judgment was also in line with the recommendations of the Dinesh Goswami Committee in 1990 and the Justice Tarkunde Committee in 1975. It is true that the Court said that its order would hold good only until Parliament made a law as envisaged in the Constitution. However, for the government to retain an executive majority in the selection process amounts to disregarding the spirit of the Court’s recommendations. An argument could be made that the CJI’s presence in the process could provide pre-emptive legitimacy to appointments and affect judicial scrutiny of errors or infirmity in the selections. Yet, when weighed against the fact that the ECI is a constitutional body that not only conducts elections but also renders a quasi-judicial role, the need for a selection process that embodies insulation from executive preponderance makes sense.

A non-partisan and independent ECI is a sine qua non for the robustness of electoral democracy. The Election Commission of India has played a seminal role in the periodic conduct of elections, which have only seen greater participation from the electorate because of the largely free, fair and convenient nature of the process. Yet, there are misgivings. In the run-up to the 2019 general election, for example, the announcement of elections was delayed for a month between February and March, allowing the government to inaugurate many projects. The Model Code of Conduct was unevenly implemented, with the ruling party receiving favourable treatment by the ECI, leading to dissent by one of the commissioners. The independent V-Dem Institute in Sweden, which compares democracies worldwide, has downgraded India to an “electoral autocracy”, citing the loss in autonomy of the ECI. With the next Lok Sabha election just months away, it should have been incumbent on the government to stay true to the Constitution Bench’s judgment and retain its recommendations in the Bill. It is for the Opposition now to ensure that the Bill is discussed and modified.

Date:14-08-23

Indian judicial data hides more than it reveals in bail cases

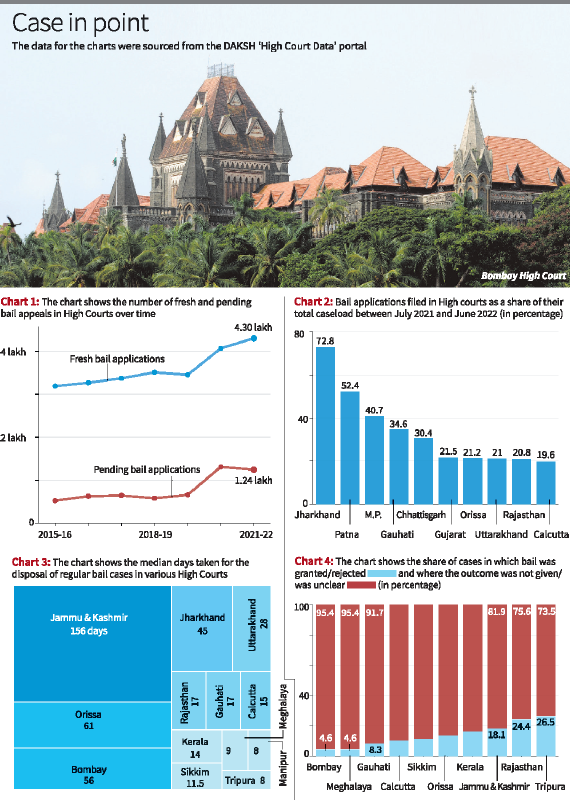

Bail outcomes were not known in 80% of cases, and the underlying offence in 77%

Consequently, the number of pending bail appeals in High Courts also surged from around 50,000 to 65,000 to between 1.25 lakh to 1.3 lakh. Chart 1 shows the number of fresh appeals and pending appeals in High Courts over time.

The data follow a July to June cycle. For instance, between July 2021 and June 2022, 4.3 lakh bail appeals were filed in High Courts.

One possible reason could be the sharp increase in cases related to the flouting of COVID-19-related lockdown norms during the pandemic. At the same time, pending bail cases piled up as the functioning of the courts was compromised during this time.

However, the exact reason cannot be ascertained from court data. The DAKSH ‘High Court dashboard’ explains that in 77% of regular bail cases, it was not possible to ascertain the Act under which the person seeking bail was imprisoned. It was not mentioned in the e-courts data of various High Courts. An analysis of 23% of cases in which the Act was mentioned shows that the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, was ranked fourth, hinting at the possibility of cases surging under this Act as the reason for more bail appeals.

The reason to understand the surge becomes paramount because in some of the States, bail appeals formed more than 30% of the caseload between July 2021 and June 2022, as shown in Chart 2. In five High Courts, i.e., in Patna, Jharkhand, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh — bail appeals formed more than 30% of their total caseload.

Across all High Courts, DAKSH analysed 9,27,896 bail cases that were filed between 2010 and 2021. Each High Court follows a unique naming pattern for bail cases. The case type abbreviation for bail application was “BA” in Bombay and “BAIL APPL.” in Kerala. Uttarakhand had the most variation among bail case types — 18 types, where the first bail application was named BA1 and in successive applications, BA2, BA3, a unique naming pattern which no other High Court followed. In all, there were 81 case types associated with bail across the 15 High Courts analysed.

The database also reveals that the median number of days taken from the filing date to the decision date for regular bail applications was 23. However, for some High Courts, the median days taken for disposal were much higher, as shown in Chart 3. The median days for disposal of regular bail cases in the Jammu & Kashmir High Court was 156, for the Orissa High Court 61 days, and for the Bombay High Court, 56 days. Given the very high number of days it takes to dispose of bail cases (which are generally considered to not require much judicial time or deliberation), the lack of data to understand the reason for delay is worrying. “Delays in resolution have the same effect as denying bail as the accused remains in prison for the duration of their trial,” the DAKSH database argues.

Finally, data regarding the outcome of bail appeals in High Courts were also missing in many cases. In close to 80% of the disposed bail cases in all High Courts, the outcome of the bail appeal — whether it was granted or rejected — was either unclear, or the outcome was missing. For instance, in the Bombay High Court, the bail outcome of over 95% of appeals was not known, as shown in Chart 4.

नफरत पर नकेल

संपादकीय

सर्वोच्च न्यायालय ने एक बार फिर नफरती भाषणों पर नकेल कसने को लेकर सरकार और प्रशासन की जिम्मेदारी रेखांकित की है। अदालत ने कहा है कि ऐसे भाषणों और अपराधों पर नजर रखने के लिए एक तंत्र बनाया जाए। अदालत ने कहा कि नफरत आधारित अपराध और नफरती बयान पूरी तरह अस्वीकार्य हैं। करीब वर्ष भर पहले भी सर्वोच्च न्यायालय ने केंद्र और राज्य सरकारों को नफरती भाषणों पर रोक लगाने का निर्देश देते हुए पुलिस की जिम्मेदारी तय की थी। अभी हरियाणा के नूंह और फिर अन्य क्षेत्रों में फैली हिंसा और नफरती बयानों तथा भाषणों के संदर्भ में दायर अपील पर उसने ताजा टिप्पणी की है। अदालत ने कहा है कि पुलिस महानिदेशकों को निर्देश दिया जाएगा कि वे एक ऐसी समिति बनाएं, जो अलग-अलग इलाकों के थाना प्रभारियों से प्राप्त नफरती बयान संबंधी शिकायतों पर गौर करके उनकी सामग्री की जांच करें और पुलिस अधिकारियों को निर्देश जारी करें। हालांकि यह पहला मौका नहीं है, जब सर्वोच्च न्यायालय ने पुलिस को इस संबंध में चौकस रहने को कहा है। दिल्ली दंगों, विधानसभा चुनावों के दौरान और फिर उत्तराखंड तथा देश के अन्य हिस्सों में आयोजित धर्म संसदों में जब नफरती भाषणों को लेकर गुहार लगाई गई थी, तब भी न्यायालय ने पुलिस की जिम्मेदारी याद दिलाई थी।

पिछले कुछ वर्षों से जिस तरह समुदाय विशेष के प्रति नफरत भरे भाषण देकर लोगों में उत्तेजना पैदा करने की कोशिशें तेज हुई हैं और इसके चलते अनेक जगहों पर हिंसा का माहौल बना है, उससे धार्मिक और सामाजिक सौहार्द काफी बिगड़ा है। जबकि संवैधानिक तकाजा है कि किसी भी समुदाय की धार्मिक स्वतंत्रता पर चोट नहीं की जा सकती, मगर पुलिस ज्यादातर मामलों में हाथ पर हाथ धरे देखी गई है। इसकी बड़ी वजह तो यह है कि ऐसे नफरती भाषण देने वालों में खुद सत्तापक्ष के लोग संलिप्त रहे हैं। स्वाभाविक ही, इससे पुलिस को सख्ती बरतने में हिचक महसूस होती रही है। जिन मामलों में सर्वोच्च न्यायालय ने पुलिस को सख्त निर्देश दिए, उनमें भी जांच और कार्रवाइयों आदि को लेकर उसका व्यवहार शिथिल ही देखा गया है। ऐसे में कहना मुश्किल है कि न्यायालय के ताजा निर्देश पर पुलिस कितनी निष्पक्षता और सख्ती बरत पाएगी। नूंह की जिस हिंसा के संदर्भ में अपील की गई थी, उसमें सामने आए चित्रों से स्पष्ट है कि पुलिस एक तरह से मूकदर्शक ही बनी रही।

पुलिस की शिथिलता और सख्ती से बचने के प्रयास की वजहें स्पष्ट हैं। सरकारों ने उसके हाथ बांध रखे हैं। फिर जहां खुद सत्तापक्ष के नेता भड़काऊ और नफरती बोल बोलते देखे जाते हैं, वहां छुटभैये नेताओं और कार्यकर्ताओं से भला कितने अनुशासन की अपेक्षा की जा सकती है? अब यह भी छिपी बात नहीं है कि राजनीतिक दल अपना जनाधार बढ़ाने के मकसद से उपद्रवी तत्त्वों को उकसाते हैं। यह संकीर्णता केवल किसी समुदाय विशेष के प्रति विष वमन तक सीमित नहीं है। जो दल जाति की राजनीति करते हैं, वे भी किसी न किसी रूप में नफरती भाषणों का सहारा लेते देखे जाते हैं। हालांकि समाज का प्रबुद्ध तबका राजनीतिक दलों की इन चालबाजियों को समझता है, मगर उसके प्रयास इतने कमजोर साबित होते हैं कि उपद्रवी तत्त्व अपनी योजनाओं में कामयाब हो जाते हैं। ऐसे में नजर आखिरकार पुलिस पर जाकर टिकती है, जिसकी जिम्मेदारी सामाजिक विद्वेष पैदा करने की कोशिशों पर अंकुश लगाने और नफरत का माहौल खत्म करने की है।