05-11-2016 (Important News Clippings)

To Download Click Here

Take Over the Living Room

Citizens need to participate more in making policy decisions related to their own surroundings

A group of enlightened citize ns, Janagraaha, in Karna taka launched a ward-level works campaign in Benga luru between December 2001and May 2002, seeking to get citizens to participate in the allocation of ward-level funds. Over 5,000 citizens across 65 wards took part, actively negotiating with corporators and the Bangalore Mahanagar Palika.

Hundreds of volunteers helped pr ovide training along with support services. The pilot demonstrated the citizens, when given institutional support, would be willing to engage with local democracy , and help make compromises, in an altruistic fashion.India’s voter rolls are anecdotally considered to be error-prone. Prior to the 2004 national elections, another group of citizens under the Mazdoor Kisan Sangharsh Samiti successfully lobbied the Chief Election Commissioner to have the voter list read out in various rural ward sabhas in Rajasthan, leading to the correction of over 7,00,000 voter entries.

In Odisha, the Centre for Youth and Social Development (CYSD) sought to gain greater citizen participation in the state budget in 2003. Even the local state media, with limited budgetary expertise and a lack of access to timely information, was reduced to simple covering summary statements of the state budget. The CYSD’s initiatives on pre-budgetary consultation led to the formation District Budget Watch Groups in six tribal districts, which prepared district charter demands and tracked the budget at the local level. However, democratic representation and citizen engagement, particularly in India’s urban areas, have always been limited. Legislators increasingly represent wards, assemblies, parliamentary constituencies with hundreds of thousands of citizens.An MP from an urban constituency typically caters to 3,00,000 more voters than a rural one). Urban voters have been left bereft, dependent on the local ward committee for pushing through real change.

This disparity is partly why our cities grow in such a haphazard fashion, their local government seeking little, if any, inputs from residents. Given this effective disenfranchisement, urban citizens are routinely indifferent and cynical about local government.

Open the Bill Gates

Even at the highest level, India’s legislative process does not statutorily mandate public participation regarding draft Bills.While ministers may at times publish such draft Bills in the public domain in the pre-legislative period, such Bills are rare and come with time-bound limits for public engagement (typically about 15 days). For instance, the Mines and Minerals Bill, 2010, was allocated seven days, and the National Sports Bill, 2011, was allocated 30 days.

Even engagements with standing committees can vary . The Department Related Standing Committee (DRSC) on the Companies Bill, 2009, saw 101 written missions and 12 oral submissions. The Right to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2009, received none at the standing committee stage. According to PRS Legislative Research, between 2008 and 2010, 1,515 subordinate legislations were laid before the Lok Sabha, of which just 44 were considered by the committee on subordinate legislation (empowered to take submissions).

In comparison, other democracies in the West have a far more robust pr ocess. The US Senate makes it mandatory to require written submissions from the public for any Bill introduced, with no restrictions on senate committees. Submissions made before any committee are available for public viewing once tabled, while any public meetings of the committees are telecast, with a few classified restrictions. After the legislation is passed, there is a compulsory post-legislative scrutiny with oversight committees reviewing the laws on a continuous basis through public hearings.

Australia holds workshops as part of regional consultations in the prelegislative stage, and after a report is finalised. Transcripts of any depositions made as part of submissions before the committees are published.We need to create mechanisms for interested registered voters to participate in local government on a regular basis, in a meaningful fashion. To support this, we need greater data collection at the ward level, particularly with respect to expenditure, voter rolls and below-poverty-line lists.

Local resident associations, neighbourhood groups and NGOs should be encouraged to link with ward committees through digital platforms and local area sabhas, as has been conducted in Kerala and West Bengal. The Kerala Municipality Act, 1999, created ward committees for each municipality with a population larger than one lakh. Such committees annually call for ward conventions that seek the help of citizens in formulating development schemes for the municipality , preparing the priority order of such schemes, ratifying the final list of beneficiaries of such schemes and mobilising voluntary service.In addition, draft Bills should undergo rigorous scrutiny by experts and ordinary citizens alike -with drafts circulated in advance to academics, trade unions, business bodies and interested citizens. Any Bill should be referred to the DRSC after such open scrutiny .

From the Pits to Pulpits

Political engagement, by citizens, will help expose them to the need for greater participation and the policy compromises inherent at every level of government. Such platforms can help government function better: helping to verify voter lists, refine BPL categorisation, provide first-responder help during disasters and bolster community policing.Rising awareness about such platforms and the benefits of such cooperation will help empower citizens, shifted them away from their current emasculated state. To build a better, credible state, we need to start at the bottom.

Varun Gandhi The writer is a BJP MP

Date: 05-11-16

Don’t mock PM Narendra Modi, don’t black out channel

A committee of the information and broadcasting ministry has recommended that Hindi news channel NDTV India be taken off the air for 24 hours for infractions of broadcast norms while reporting on the terror attack on Pathankot. The ministry should refrain from acting on the recommendation, on two counts. One, it should not make hollow rhetoric out of the Prime Minister’s ringing endorsement of the role the media plays in making democracy work, delivered recently at a function to hand out journalism awards. Two, unlike during the Mumbai attack of 2008, when live television coverage of operations probably helped the handlers of the terrorists to decide their next course of action, reportage of the Pathankot carried no details of ongoing counterterror measures.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi not only championed media freedom but also pointed to the importance of editorial validation that is missing in social media but is key with regular media. If the organised media does not meet the information requirements of the public at large, irresponsible rumours are likely to spread on social media. The charge that the news channel ‘disclosed’ that the air force base contained MiG warplanes, ammunition and mortars is ridiculous. In the absence of such disclosure, does the committee imply, those who planned the attack would have expected to find sailboats and no weapons or ammunition? To say that by disclosing that the base contained a school, it endangered civilians is to assume that the terrorists wandered into the Pathankot base, knowing nothing about what all the base contained, instead of scoping out the place in advance and mounting a pre-planned attack.

Yes, the media must show restraint while covering matters of national security. This is not the way to make the point.

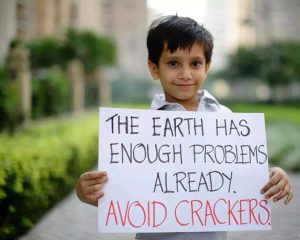

बचना ही होगा जहर से

The quality of justice

Creating an All India Judicial Service would make judiciary more accountable, professional and equitable.

Here, the judiciary must introspect on some issues. For instance, why are there always 20 per cent vacancies in the courts? Vacancies are never filled in time. Why do these positions remain empty? The answer is simple. Because the judiciary is unable to attract talent. To compound things further, today the subordinate judiciary depends entirely on state recruitment. But the brighter law students do not join the state judicial services because they are not attractive. With no career progression, no one with a respectable Bar practice wants to become an additional district judge, and deal with the hassles of transfers and postings. Consequently, the quality of the subordinate judiciary is by and large average, although there are some bright exceptions. By extension, at least one-third of high court judges elevated from the subordinate judiciary are also mostly average. As a result, the litigants are left to suffer.

Ajit Prakash Shah

Date: 04-11-16

Faith And Its Limits

Religious freedom under the Constitution is conditional, open to state intervention.

When THE SUPREME Court of India upheld the validity of police bans on the Anand Margi practice of performing tandava nritya, community leaders saw in it denial of their constitutionally protected right to religious freedom. The same was the reaction of Jain saints when the Rajasthan High Court last year declared illegal the practice of santhara. And, now the provision for religious freedom under the Constitution is being invoked by Muslim theologians opposing the petitions of some divorced Muslim girls in the apex court seeking a ban on what is called “triple talaq”. These and many other similar cases point out to a mistaken belief in the society that the Constitution furnishes a blanket protection to all sorts of archaic social practices bearing a religious tagline.

In Part III of the Constitution, which assures people certain fundamental rights, Article 25 proclaims that “all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion”. What people fail to notice is that this proclamation is prefixed with the words “subject to public order, morality, health and to the other provisions of this Part”, which set conditions precedent for the legal protection of religious practices of any community. The closing words of this prefatory rider in Article 25 virtually constitute a subordination clause placing other fundamental rights mentioned in Part III over and above the right to religious freedom. Among those other fundamental rights is the right to equality before law and equal protection of laws — assured at the outset and elaborated in later articles to mean, inter alia, that the state shall not deny equal protection of laws to any person or group of persons on the basis of religion alone.

“Give what is Caesar’s to Caesar and what is God’s to God” is said to be part of Jesus Christ’s teachings. Realising that in the Indian tradition too much is believed to be God’s than Caesar’s, Constitution-makers found it necessary to clarify the limits of people’s religious freedom. The clarification came in the form of a declaration in Article 25 that “nothing in this article” shall prevent the state from regulating or restricting by law any “economic, financial, political or other secular activity which may be associated with religion”.

What is, then, the yardstick to decide if any particular tradition is a genuine religious practice or a “secular activity associated with religion”? The Supreme Court has generated a litmus test for this purpose — is it an “essential practice integral to” the concerned religion? And, to find out the true position about it, the court has been looking into authentic texts and their interpretations acceptable unanimously to all of its followers or at least to their overwhelming majority.

As regards the Muslims, under Islamic jurisprudence religious precepts are placed in two separate compartments — ibadaat (spiritual matters) and muamlaat (temporal matters) — and in either of these, there is a further categorisation. Practices specifically enjoined by the Quran (divine book) or Hadith (Prophet’s sayings) are farz or wajib — obligatory absolutely in the first and generally in the latter case. All other actions mentioned in religious books are either mustahab (recommended) or jaez (permissible). Going by these classifications, religious practices that are farz or wajib for the Muslims will be covered in India by the religious freedom clause of the Constitution. Even what is recommended by religious texts can perhaps be claimed to fall under that protective umbrella, but not what is merely permissible — and certainly not any abominable practice that according to Muslim theologians themselves is bidat (against true religion).

The provision for religious freedom under Article 25 closes with a final clarification that “nothing in this article” shall prevent the state from making laws providing for social welfare and reform. In its deeper meaning this assertive clause — applicable to all communities — engenders a fiduciary obligation for the custodians of state authority to move in this direction as and when necessary.